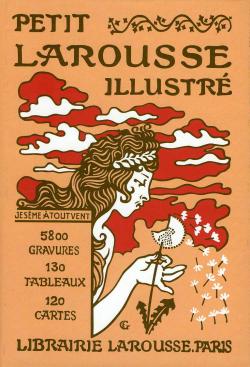

the 1905 edition of Le Petit Larousse illustré, a French-language encyclopaedic dictionary published by the Éditions Larousse

In 1890, Eugène Grasset (1845-1917) designed the image of la Semeuse (the Sower) blowing dandelion seeds, which accompanies the motto of the Éditions Larousse, Je sème à tout vent (I sow to the four winds).

The word dandelion is from French dent de lion, in Medieval Latin dens leonis, meaning lion’s tooth, from the toothed outline of the leaves.

The word is first attested (in its French form) in 1513, in Eneados, a translation into Middle Scots of Virgil’s Aeneid by the Scottish poet and bishop of Dunkeld Gavin Douglas (circa 1476-1522):

The flour delice furth spred his hevinly hew,

Flour dammes, and columby blank and blew;

Seyr downis smaill on dent de lion sprang,

The ȝing grene blomyt straberry levis amang.

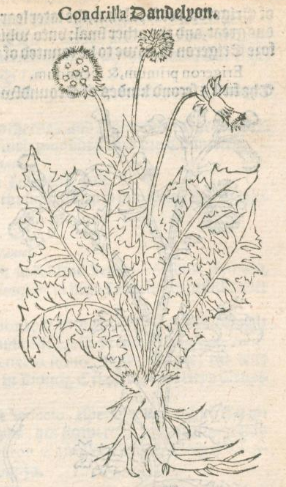

The forms dandelion and dandelyon are first recorded in A Niewe Herball, Or Historie of Plantes (1578), the translation by the English botanist and antiquary Henry Lyte (1529?-1607) of the French translation of Cruijdeboeck, first published in 1554 by the Flemish botanist and physician Rembert Dodoens (1517-85).

Condrilla Dandelyon, from A Niewe Herball, Or Historie of Plantes (1578)

In French, dandelion is pissenlit, a noun composed of a conjugated form of the verb pisser, to piss, the preposition en, meaning in, and the noun lit, bed, because this plant was formerly well known for its diuretic properties.

The word pissenlit is first recorded in the mid-15th-century book Les Évangiles des Quenouilles (The Distaff Gospels), a collection of popular beliefs held by old women. It is recommended in this book to rub warts with the milky juice of a dandelion leaf in order to dry them.

The French expression manger les pissenlits par la racine, literally to eat the dandelions by the root, corresponds to the English to be pushing up (the) daisies, that is, to be dead and buried. It was first used by Victor Hugo in his novel Les Misérables (1862); the author wrote that the Paris urchin had his own metaphors:

être mort, cela s’appelle manger des pissenlits par la racine (to be dead, that is called to eat (some) dandelions by the root).

Similarly, English has the noun pissabed, a compound of the verb piss, the preposition a, meaning in, and the noun bed. In The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes (1597), the herbalist John Gerard (circa 1545-1612) wrote, after discussing several Greek and Latin botanical names of the dandelion:

Diuers of the later Phisitions do also call it Dens Leonis, or Dandelion: it is called in high Dutch Kalkraut: in low Dutch Papencruit: in French Pissenlit ou couronne de prestre [= or priest’s crown], or Dent de lyon: in English Dandelion, and of diuers Pisseabed.

(The learned writers of herbals assumed that different types of readers would use their books, including those who would have been familiar with folk knowledge. This is why the slang or popular names were listed together with the apothecary and botanical names.)

The name pissabed is still in use. For instance, the Irish playwright, novelist and poet Samuel Beckett (1906-89) wrote, in Watt (1953):

Of flowers there was no trace, save of the flowers that plant themselves, or never die, or die only after many seasons, strangled by the rank grass. The chief of these was the pissabed.

This name is also used derogatorily to mean bed-wetter (as was French pissenlit), and as a more general term of abuse. In the latter sense, it is also an adjective; for example, on 12th October 1820, the English poet George Gordon Byron (1788-1824) wrote the following from the Italian city of Ravenna to his publisher John Murray in London (the English poet John Keats (1795-1821) was a principal figure of the romantic movement):

Ravenna, 8bre 12°, 1820.

By land and sea carriage a considerable quantity of books have arrived; and I am obliged and grateful: but ‘medio de fonte leporum, surgit amari aliquid,’ &c. &c.; which, being interpreted, means,

I’m thankful for your books, dear Murray;

But why not send Scott’s Monastery?

the only book in four living volumes I would give a baioccolo to see—’bating the rest of the same author, and an occasional Edinburgh and Quarterly, as brief chroniclers of the times. Instead of this, here are Johnny Keats’s p—ss a bed poetry, and three novels by God knows whom, except that there is Peg Holford’s name to one of them—a spinster whom I thought we had sent back to her spinning. Crayon is very good; Hogg’s Tales rough, but RACY, and welcome.

In French, pissenlit is comparable to the noun chienlit, in which chie is a conjugated form of the verb chier, to shit. It was first used to designate a person who defecates in bed by the French satirist François Rabelais (circa 1494-1553) in The Very Horrific Life of the Great Gargantua, Father of Pantagruel (La vie très horrifique du grand Gargantua, père de Pantagruel – 1534). In the 18th century, it came to denote a masked person participating in a popular carnival, then by extension in the 19th century a carnival, hence its current sense: havoc, chaos.