No verb for to eat in the Romance languages is directly derived from the standard classical-Latin verb eděre (the infinitive was also ēsse), from which is derived English edible, and with which English eat is cognate.

The Latin verb coměděre/comesse, a compound of the intensive prefix com- and of the verb eděre/ēsse, originally meant to eat up entirely, and came to be used in the neutral sense of to eat. It is the origin of the French adjective and noun comestible, meaning edible, and of the Spanish and Portuguese verbs comer, to eat.

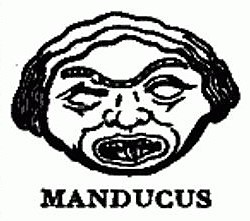

But to eat in the other Romance languages is manger in French, menjar in Catalan, mânca in Romanian and mangiare in Italian. These verbs are from Latin mandūcāre, itself a lengthened form of manděre, to chew. Because of its connotation of chomping, mandūcāre was originally found mainly in Latin comic and satiric writings. In fact, this verb is from manděre through the noun mandūcus, literally a guzzler, also a ludicrous masked figure representing a person chewing, used in processions and in comedies to excite merriment.

mandūcus – from Dictionnaire illustré latin-français (1934), by Félix Gaffiot

However, mandūcāre too came to be used in the neutral sense of to eat; according to the Roman biographer and historian Suetonius (circa 69-circa 150 AD), the Emperor Augustus himself wrote the following in a letter to his stepson Tiberius:

duas bucceas manducavi (I ate two mouthfuls)

The noun buccĕa, mouthful, used by Augustus, is from bucca, which originally denoted the cheek puffed or filled out in speaking, eating, etc. It came to mean the mouth, eventually replacing the classical-Latin noun ōs–ōris (cf. English words such as oracy, oral and oracle).

(Similarly, the familiar French verb bouffer, to eat (greedily), originally meant to puff one’s cheeks out.)

From Latin bucca, mouth, French uses bouche, Spanish, Portuguese and Catalan boca, and Italian bocca.

Alone in the Romance languages, Romanian uses gură, from Latin gŭla, which meant throat, gullet, palate, mouth, and by extension gluttony, gourmandising. This Latin word has also survived in French gueule, which denotes the mouth of an animal, and is an offensive term for a person’s mouth.

As József Herman explained in Le latin vulgaire (Presses Universitaires de France, 1967), these linguistic facts show that, in Latin, short words having complicated irregularities in their forms, such as eděre/ēsse and ōs–ōris, eventually gave way to simpler alternatives with more regular patterns and longer phonetic individualities, such as coměděre/comesse, mandūcāre and bucca. The latter were also more colourful and forceful.

For example, the verb eděre/ēsse was irregular and included several monosyllabic forms, some of which being identical to inflections of the verb to be (the infinitives were ēsse (with long e), to eat, and ĕsse (with short e), to be). Moreover, the opposition between long and short vowels eventually ceased to be distinctive.

In addition to these drawbacks, writes Joseph B. Solodow in Latin Alive: The Survival of Latin in English and the Romance Languages (Cambridge University Press, 2010), eděre/ēsse must have appeared weak in content, without force or flavour. The preferred words, coměděre/comesse and mandūcāre, were more colourful than eděre/ēsse: they presented to speakers a vivid image in place of a neutral term.

Until, they themselves, from steady use, became ordinary too…

NOTES

The English noun manger, denoting a long trough from which horses or cattle feed, is from Old French mangeure (Modern French mangeoire), from the French verb manger, to eat.

The French verb démanger, to itch, is a compound of the intensive prefix dé- and of the verb manger; it literally means to eat up.)

In English, the verb manducate and the noun manducation are based on mandūcāre, and the noun mandible is derived from manděre.

Le latin vulgaire was translated as Vulgar Latin by Roger Wright, and published by the Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000.

Strange that I was looking for exactly the same question : “to eat” in romance languages ! Many thanks for the post.

LikeLike