The Oxford English Dictionary (OED – 2nd edition, 1989) defines the phrase tennis, anyone?, also anyone for tennis?, who’s for tennis?, etc., as follows:

a typical entrance or exit line given to a young man in a superficial drawing-room comedy, used attributively of (someone or something reminiscent of) this kind of comedy. Also in extended uses.

The earliest occurrence of the phrase that the OED has recorded is from Playwright at Work (New York: Harper, 1953), by the English playwright and theatre director John van Druten (1901-1957):

There is no average Mr. and Mrs. Blank, at all. An attempt to draw one—for example, the ordinary middle-class husband or wife—will lead you into the pit of emptiness, and you will emerge with something as unreal as the juveniles in plays who come in impertinently swinging tennis rackets, and when the time for their exit arrives, make it with the remark: “Tennis, anyone?”

However, the earliest occurrence of the phrase that I have found is not related to the theatre; it is from The Magic Photograph, by George Randolph Chester, a short story evoking the pastimes of members of the leisured class during a stay at a country house, published in the Illustrated magazine of The Daily Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) of Sunday 17th May 1908:

Ralph Wyatt [spoke] from the porch railing, where he sat idly swinging his tennis racquet. […]

[…]

“I confess myself handicapped,” said Ralph Wyatt, lifting his angularity from the rail as he passed the photograph to Tommy Farwell, “and I want to forget my sorrows. Who’s for tennis?”

As he held out his hand to assist Nellie Taggart from her rocking chair, that young lady was obviously elected for tennis also.

It is, however, interesting that the above-quoted short story, The Magic Photograph, evokes the pastimes of members of the leisured class during a stay at a country house, because it is precisely that type of activities, protagonists and places that the stage plays in which occurs the phrase deal with—as explained by Harry A. McCrea in the column So I’m Told, published in The Canton Repository (Canton, Ohio) of Sunday 6th July 1947:

Vincent Richards, the head man in professional tennis, says the pros are eliminating the term “love”—the tennis term, that is. Richards says it detracts from the dignity of the game.

Richards is just a spoilsport. A whole school of English high comedy has been built on the double meaning of the word. Plays such as “Let Us Be Gay,” in which the scene is laid at an English country house where a weekend party is in progress. Soda is fizzing, butlers are buttling and monocles are popping when a robust babe makes her mis-en-scene and asks: “Tennis, anyone?” Right away you see the playwright is building up to a two-pronged epigram about love.

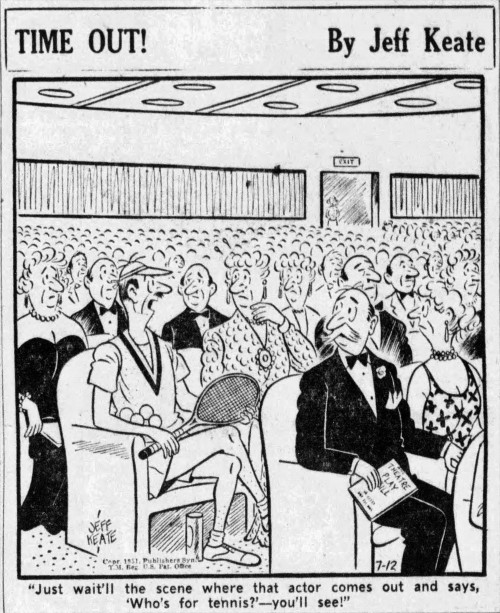

In the following Time Out! cartoon, published in several U.S. newspapers on Thursday 12th July 1951—for example in the Daily Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pennsylvania)—Jeff Keate satirises the stage plays in which the phrase occurs; in a playhouse, one of the spectators, dressed in a tennis outfit, and holding a tennis racquet and tennis balls, is saying to one of his bemused neighbours:

“Just wait’ll the scene where that actor comes out and says, ‘Who’s for tennis?’—you’ll see!”

The following are the other earliest occurrences that I have found of the phrase used in one case in a stage play, in the others with explicit reference to the theatre:

1-: From Ain’t Love Grand?, a stage play by Pauline Peterson, published in The Leader-Post (Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada) of Saturday 8th December 1934:

—The plot of the story is the difficulty that Judy Lane, a young heiress, has in obtaining her inheritance. Dona, Judy’s best friend, is a happy-go-lucky girl, always kind and willing to help; Claude is a young, carefree man, very much in love with Dona:

ACT I

Scene IPlace: Front room of the Lane home in Rawsley, a fairly large city. The room is furnished tastefully with the usual furniture—small table, deep chairs, lamps, piano, rugs, etc.

[…]

Dona—Everything’s a mystery to me! Peggy is supposed to be kidnapped and she walks in! Judy’s acting queer! And Peggy’s just as queer! I wonder that’s [misprint for ‘what’s’] next?

Claude—Oh, well, let’s not trouble our minds about it! How about a game of tennis?

Dona—All right—anything to pass the time away. (Exit Dona and Claude.)

2-: From Fugitive from a Racquet: Humphrey Bogart Escapes from Tennis-Playing Juvenile Roles, an interview of Humphrey Bogart 1 by Carlisle Jones, published in Screen & Radio Weekly, itself published in The Detroit Free Press (Detroit, Michigan) of Sunday 24th May 1936:

Humphrey Bogart, the menacing gangster chief of “The Petrified Forest,” […] went “tough” primarily to get away from tennis racquets. He used to be pegged by New York producers as a romantic juvenile, which Bogart believes is an actor’s lowest estate. To him a racquet, perennial prop for leading juveniles, is a symbol of those unhappy days.

[…]

“It’s like this,” said Bogart […]. “The playwright gets five or six characters into a scene and then can’t figure out a way to get rid of all but two of them. What does he do? He drags in the handsome young juvenile, tennis racquet in hand, who says:

“‘How about a game of tennis?’

“That makes it easy for everyone. The players accept the suggestion. The leading lady, who has a love scene coming up with the leading man on the next page, says she is tired. The others go off and the stage is all set for the big clinch.

“It represents no great opportunity for the juvenile but it makes it handy for the author.”

[…]

“Of course, it isn’t always a tennis racquet,” he went on. “It can be done with golf clubs or a baseball bat or a pair of dice. But playwrights have a weakness for tennis. It can be played, presumably, just off stage, so when he gets stuck with the dialog between the leading lady and her lover, all he has to do is have the juvenile come back in and persuade one or both of these to ‘come out and point the game.’ I’ve seen juveniles get rid of eight or 10 characters that way in a single evening.”

[…]

“Tennis is a playwright’s idea of the proper game for the juvenile to play,” he added. “He wears clean white flannels, sneakers and has a chance to show the hair on his chest. It’s supposed to be good theater.

“Lately they’ve been getting into the habit of ending the scene whenever the author is stuck with too many characters on the stage. Now we have plays with 17, 18 or 47 acts, revolving stages and sets that move up or down or around. The tennis gag is much simpler. I must have saved producers millions of dollars by dragging off the surplus actors with that magnificent line: ‘How about a game of tennis?’”

[…]

“I used it when I played with Mary Boland in ‘Meet the Wife,’” he recalled.

[…]

“Let’s finish this tomorrow,” he suggested. “How about a game of tennis?”

[…]

“That damned line still haunts me,” he said. “Hope you don’t mind.”

1 Humphrey DeForest Bogart (1899-1957) was a U.S. actor—cf. also origin of the verb ‘bogart’ (to monopolise) – ‘here’s looking at you’ (used as a toast in drinking) – notes on various acceptations of the term ‘rat pack’.

3-: From Hollywood Sights And Sounds, by Robbin Coons, about the U.S. actress Rosalind Russell (1907-1976), published in several U.S. newspapers in October 1940—for example in the Big Spring Daily Herald (Big Spring, Texas) of Tuesday the 15th:

The Russell girl came to Hollywood with a stage background which included drama, farce, comedy, all phases of theatre. She fell into second leads almost immediately—the sort of stilted society roles she tabs as the “Who’s for tennis?” or “Jack looks peaked today” variety.

4-: From the review by John Rosenfield of Our Hearts Were Growing Up, a 1946 U.S. comedy film directed by William D. Russell (1908-1968), starring Gail Russell (Elizabeth L. Russell – 1924-1961)—review published in The Dallas Morning News (Dallas, Texas) of Thursday 22nd August 1946:

A little sequence but finely acted is Miss Russell’s disavowal of further interest in her gridiron star. Director Russell gets first-class satire out of a Philip Barryish 2 stage comedy with the ingenue lead making a chipper “Tennis, anybody?” entrance on her mother’s tete-a-tete with a lover.

2 This is an allusion to the U.S. playwright Philip Barry (1896-1949).

5-: From The Canton Repository (Canton, Ohio) of Tuesday 15th June 1948:

Anyone for Tennis?

By Harry A. McCreaI first saw Reginald Calthorpe many years ago when I attended a Lonsdale play. He had the role of a callow young Oxonian weekending at an English country house. Rigged out in a tennis outfit and languidly swinging a racket, he oozed onto the stage and asked in his best Balliol accent, “Anyone for tennis?”

6-: From the column The Cinema, by Dick Pitts, published in The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina) of Saturday 7th August 1948:

It was the stage version of “The Petrified Forest” which brought Bogart to the rumpled-hair, cigarette-in-lip, clipped-speech gunman role which won him lasting fame and a fat Hollywood contract.

“It took me that long,” he recalled, “to discover that I could act without a tennis racket in my hand.”

Today Mr. Bogart, having long out-grown the tennis-anybody period, plays a tight-lipped character in Warner’s “Key Largo.”

7-: From an article, apparently written by the British-born U.S. comedian Bob Hope (Leslie Townes Hope – 1903-2003), about an industrial dispute at the Metropolitan Opera, which “would decide whether or not the Met would open this fall”—article published in the Chicago Daily Sun-Times (Chicago, Illinois) of Friday 10th September 1948:

What would this fall be without the opera? […]

[…]

The guys I would feel sorry for are all those spear-carriers who’d have to get dramatic parts in other shows. Picture 40 of them running on the stage at one time and yelling in unison, “Anyone for tennis?”

8-: From an interview of Humphrey Bogart by Erskine Johnson, published in several U.S. newspapers in September and October 1948—for example in The Daily Home News (New Brunswick, New Jersey) of Thursday 16th September:

Bogart laughed. “I used to play juveniles on Broadway and came bouncing into drawing rooms with a tennis racket under my arm and the line: “Tennis anybody?” It was a stage trick to get some of the characters off the set so the plot could continue. Now when they want some characters out of the way I come in with a gun and bump ’em off.”

9-: From a portrait by John Rosenfield of the U.S. novelist, playwright and short-story writer William Saroyan (1908-1981), published in The Dallas Morning News (Dallas, Texas) of Sunday 30th January 1949:

Saroyan scandalized the morose academicians by daring to be happy. His places and people were not the stuff of the slick magazines for the prosperous upper middle class. Not trivial fables of the “Tennis, anybody?” type came from him.

10-: From an interview of Errol Flynn 3 by Hedda Hopper 4, published in several U.S. newspapers in May 1949—for example in the Chicago Daily Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) of Sunday the 29th (in the following, Errol Flynn talks of the British and American actress and singer Greer Garson (1904-1996)):

“A funny thing, we never knew each other in those days, but Greer was playing in repertory in Bridgehampton in England at the same time I, too, was just starting out in the theater in Northampton, which is only about 30 miles away. I used to play broken old fellows with bald wigs, who came on stage and said, ‘Your carriage, sir.’ The only thing I missed was running on stage wearing a beret and blazer, and shouting, ‘Tennis, anybody?’”

3 Errol Flynn (Leslie Thomas Flynn – 1909-1959) was an Australian-born U.S. actor.

4 Hedda Hopper (born Elda Furry – 1885-1966) was an American gossip columnist and actress.