In ‘greasy spoon’: early instances; connexions with German, I have explained that the earliest instance of the term greasy spoon, denoting a cheap, dingy restaurant, occurs—apparently as a translation from German—in a correspondence from Rendsburg, in present-time northern Germany, published in The Times (London, England) of Tuesday 3rd September 1850.

Likewise, the earliest occurrence of the obsolete synonymous term dirty spoon is explicitly a translation from German. It is from a sketch of artistic life in Rome, in Sand and Canvas; a Narrative of Adventures in Egypt, with a sojourn among the Artists in Rome (Charles Gilpin – London, England, 1849), by one Samuel Bevan—the German phrase zum schmutzigen Löffel translates as at the dirty spoon:

The Gabbione, the Falcone, and the Scalinata, are well-known houses, each remarkable in some way or other. The first, which was once a banking-establishment, is a cellar under a house, near the Fountain of Trevi, and is famed for its good wines, delicious water, and cheapness, but it has withal an appearance so murky and so very far removed from cleanliness, that the Germans have bestowed upon it the appellation of the “Dirty Spoon.”*

* Zum schmutzigen Löffel.

However, I have discovered that, in the USA, dirty spoon did not originally designate eating-places, but brothels and squalid lodging-houses, particularly in New York City.

The term first occurs as the proper name of a brothel on Cherry Street, New York City, as reported by The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) of Thursday 1st May 1862—I am unsure of whether the fact that “the girls were all, with one exception, Germans” indicates that the name is of German origin:

Our New York Letter

Special Correspondence of the Inquirer.

New York, April 30, 1862.

[…]

A notorious brothel, known as the “Dirty Spoon,” No 59 Cherry street, was effectually cleaned out by the police this morning. The landlord, John Smith, ten women and twenty-six men were arrested. The girls were all, with one exception, Germans, and the men were representatives of nearly every nation on earth. The latter were all discharged, except the proprietor, who was held to bail in $500, while the girls were committed for examination.

(Reporting on this police raid the day before, Wednesday 30th April 1862, The World (New York City, N.Y.) used a euphemism: it said that the Dirty Spoon, at 59 Cherry Street, was “a dance-house”.)

This brothel closed not long afterwards, since The New York Times (New York City, N.Y.) of Monday 26th February 1866 reported the following:

Fire in Cherry-street.—Last evening, at about 10½ o’clock, Officer Oates, of the Fourth Precinct, discovered a fire bursting out through the window of the second floor of the two-story frame building No. 59 Cherry-street, formerly enjoying the name of “The Dirty Spoon,” but latterly occupied by Tiernan & Co., dealer in cottons, who had a stock of baled and loose cottons on hand.

The name reoccurs in One Poor Girl: The Story of Thousands (J. B. Lippincott & Co. – Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1869), in which the American journalist and author William Wirt Sikes (1836-83) evokes the slums of New York City. In the following passage, he describes the Dirty Spoon—“or Gotham court, as it is otherwise called”:

There are grades of squalor. The people who inhabit those fragrant localities known as Murderer’s alley and the Dirty Spoon, feel themselves far higher in the social scale than “them low creeters” in the Five Points and Bilker’s Hole. In fact, it is a common practice with the people of various neighborhoods where the heathen are thickest, and where beggars and thieves hold high carnival after dark, to throw verbal mud at each other, after the fashion of rival towns in the West. Water street looks upon it as a deep disgrace to dwell in the Five Points; and vice versa. But if there is a Belgravia of low life, no doubt its locus in quo is the Dirty Spoon.

[…]

The Dirty Spoon is the title given to the huge tenement building at Nos. 36 and 38 Cherry street, with the alleys that flank it on either side, and by which the occupants of the building reach their several places of entrance. How many people reside in this monster hive it is impossible to say: probably, more than a thousand. It is the largest house of its class in the city.

Ten years later, the Dirty Spoon reappears as the name of a lodging house on Oliver Street, New York City—the following is from The Sun (New York City, N.Y.) of Friday 23rd May 1879:

Fourth Ward Lodgings.

The Sort of Tramps’ Resort that the Police Broke Up in Oliver Street.Capt. Petty of the Oak street police, with Detectives John Keirns and Gilbert Carr, marched into the Tombs Police Court yesterday with sixty men and women whom he had arrested in Bridget Donnelly’s lodging house at 68 Oliver street, at 5 o’clock in the morning. The house in question is an old-fashioned three-story and basement red brick building. The once green shutters are nailed up, the black door is cracked and blistered, and the glass panels are broken. The basement is divided up in narrow bunks. In a cellar beneath is an accumulation of ashes, broken bottles, and damp straw. To gain access to this cellar it is necessary to go through a trap door and down a crazy ladder. Here the lowest tramps of both sexes were permitted to sleep for a consideration of from five cents to two cents. The bunks in the basement were let at from ten to twenty cents. The third and fourth floors and the garret, fitted up with narrow beds, were worth thirty cents a night to a lodger. In the rear yard were three covered sheds, in which a quantity of loose straw was scattered, and for this accommodation Mrs. Donnelly exacted whatever pennies applicants were able to give. Mrs. Donnelly’s two daughters live in the house—well-dressed children, one of whom has a governess to teach her French and music.

“The Dirty Spoon” has been notorious for many years. During the war it was a dance house and gambling den. It was in the basement that a sailor in a drunken fight was shot dead and his body thrown into the cellar, where it was allowed to remain two weeks before the authorities were notified. On the stoop of the house a police officer, who was disliked by the inmates, was stabbed in the back and died instantly, his murderer escaping.

The term occurs again as one of the nicknames given to a brothel in Galveston, Texas, according to The Galveston Daily News of Tuesday 10th June 1879:

The Social Evil.

Mr. Tom Connors and his wife were put on trial for keeping a house of ill-fame. Some of the witnesses called the house the dirty spoon, the last chance and the cabbage factory. A severance of the case was had, Mr. Connors being put on trial. The jury, after being out a very short time, returned a verdict of $50 and costs. This makes the fifth conviction Capt. Atkins has secured of disreputable houses, for which discharge of duty the moral people of Galveston owe him a debt of gratitude. Others following this reprehensible course of life should take warning, as Capt. Atkins is determined to do his full duty, and clean all such houses out of the prescribed limits.

In How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York (Charles Scribner’s sons – New York City, N.Y., 1890), the Danish-American journalist, social reformer and social documentary photographer Jacob August Riis (1849-1914) mentioned a house named the Dirty Spoon in Blind Man’s Alley:

Some idea of what is meant by a sanitary “cleaning up” in these slums may be gained from the account of a mishap I met with once, in taking a flash-light picture of a group of blind beggars in one of the tenements down here. With unpractised hands I managed to set fire to the house. When the blinding effect of the flash had passed away and I could see once more, I discovered that a lot of paper and rags that hung on the wall were ablaze. There were six of us, five blind men and women who knew nothing of their danger, and myself, in an attic room with a dozen crooked, rickety stairs between us and the street, and as many households as helpless as the one whose guest I was all about us. The thought: how were they ever to be got out? made my blood run cold as I saw the flames creeping up the wall, and my first impulse was to bolt for the street and shout for help. The next was to smother the fire myself, and I did, with a vast deal of trouble. Afterward, when I came down to the street I told a friendly policeman of my trouble. For some reason he thought it rather a good joke, and laughed immoderately at my concern lest even then sparks should be burrowing in the rotten wall that might yet break out in flame and destroy the house with all that were in it. He told me why, when he found time to draw breath. “Why, don’t you know,” he said, “that house is the Dirty Spoon? It caught fire six times last winter, but it wouldn’t burn. The dirt was so thick on the walls, it smothered the fire!” Which, if true, shows that water and dirt, not usually held to be harmonious elements, work together for the good of those who insure houses.

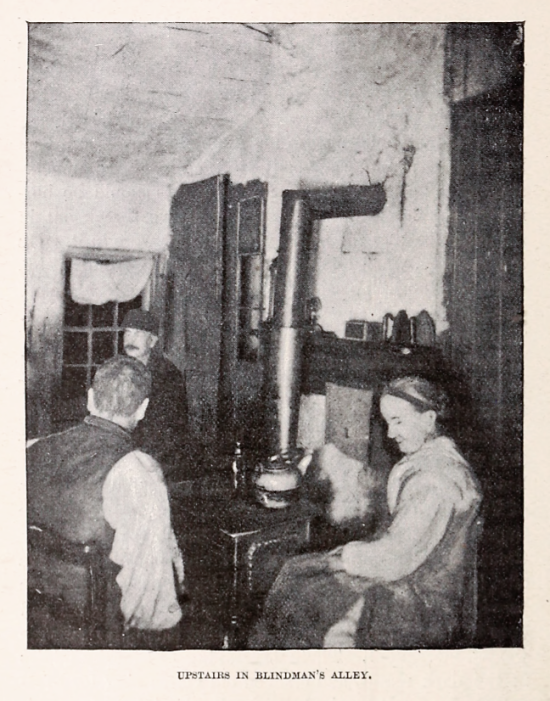

Upstairs in Blindman’s Alley—photograph by Jacob A. Riis—from How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York (1890):

The term dirty spoon appeared as the proper name given to an establishment where alcoholic drinks may be bought and drunk in The Boston Herald (Boston, Massachusetts) of Sunday 15th April 1894, which explained that the liquor law was a dead letter in Lewiston, Maine:

The kitchen bar harassed at different times by the law, but surviving all such interruptions, is now gradually giving way to the polished bar, which thrives unmolested by the guardians of the peace.

From the standpoint of the honest advocate of temperance the present state of affairs is deplorable, for the large amount of liquor drunk and the intemperance of the community is undisputed.

The old resorts other than the kitchen bars are all open. Among others are Mugg’s Landing, the Hoffman House, Home Base, the Midway, Hell Gate, the Side Pocket, the Flying Yankee, the Rat Pit, the Life Saving Station, Quebec Castle, Crow’s Nest, Dirty Spoon, Ward Eight, Shamrock, Thistle Flower Garden, Patrol Box, Chinese Wall, the Roost, Hole in the Wall, Red Front, Orange Blossom, Long Reach and a hundred more that have not been named.

The earliest American-English use of dirty spoon as a designation of an eating-house is from The Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois, USA) of Wednesday 6th October 1897:

REPORTERS EAT PURE FOOD.

Well Laden Tables Despoiled at Health Exposition.Miss Nellie Dot Ranche gave a supper of pure and wholesome food to the press last night at the health exposition. She wished its members to know a moral and elevating supper when they saw one, and to spread the knowledge abroad, that one more ray of sunshine might penetrate into this dark world.

And the press came; each paper sent the reporter who was the hungriest looking. The row of newspaper men stood timidly before the well-laden table of her whose mission is grub. No one dared sit down. At last one of the guests who had a booth in the exposition made a break for a seat; he mistook the reluctance of the reporters for suspicion, and determined at whatever cost to himself to show that the health food people dared eat their own wares.

But it was not suspicion on the part of the newspaper men; they only felt their own unworthiness to associate on terms of familiarity with pure food. In “The Dirty Spoon,” or in “The Sewer,” or in some other restaurant such as reporters are used to, they sit down with the utmost applomb [sic], and even, at times, with a slight feeling of moral superiority. But here in the presence of the pure and the wholesome, they remembered the “still, white innocence of childhood,” as James O’Donnell Bennett1 poetically puts it, and many a one turned aside with moist eyes, remembering those beautiful lines in Young Lochinvar:

And now I am come to this beautiful maid,

To tread but one measure, drink one lemonade.2

1 James O’Donnell Bennett (1870-1940) was an American author, and a reporter for Chicago newspapers.

2 This is a parody of a passage from Marmion: A Tale of Flodden Field (1808), a narrative poem by the Scottish novelist and poet Walter Scott (1771-1832); in the passage in question, Lochinvar, a brave knight, arrives unannounced at the bridal feast of Ellen, his beloved.