The American-English phrase like shooting fish in a barrel means very easy to accomplish, sometimes with an implication of unscrupulousness—synonym: like taking/stealing candy from a baby.

The earliest instance of the image that I have found is from the following list of miscellaneous news and commercial advertisements, published in the Neodesha Daily Derrick (Neodesha, Kansas) of Friday 29th April 1898—however, here, shooting fish in a barrel might not mean very easy, but might be a metaphor for the bombardment on 27th April of the city of Matanzas by the U.S.-Navy ships that were blockading Cuba at the beginning of the Spanish-American War, a war between Spain and the United States in the Caribbean and the Philippines in 1898:

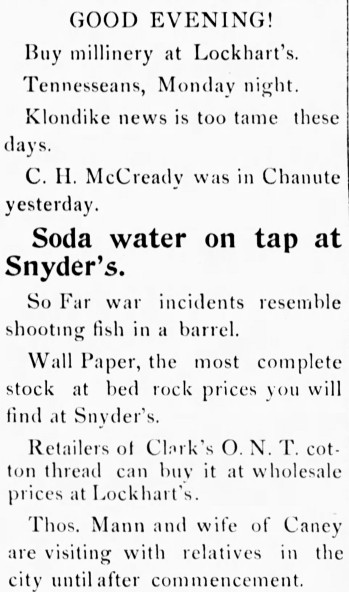

GOOD EVENING!

Buy millinery at Lockhart’s.

Tennesseans, Monday night.

Klondike news is too tame these days.

C. H. McCready was in Chanute yesterday.

Soda water on tap at Snyder’s.

So Far war incidents resemble shooting fish in a barrel.

Wall Paper, the most complete stock at bed rock prices you will find at Snyder’s.

Retailers of Clark’s O. N. T. cotton thread can buy at wholesale prices at Lockhart’s.

Thos. Mann and wife of Caney are visiting with relatives in the city until after commencement.

[&c.]

The earliest unambiguous instance that I have found of shooting fish in a barrel in its current sense is from the column By the By!, in The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) of Tuesday 11th February 1902:

“Funny, isn’t it,” said an expert taster of tea who is employed in one of New York’s largest importing houses, “that a whisky drinker like our friend here could not, to save his life, tell the grade and brand of liquor he takes after he has had two drinks?” “Oh, yes I can,” replied the gentleman addressed, and what is more I can tell the brands of more than two kinds of whisky and can do so with absolute certainty.” “Bet you can’t,” said the tea man. “Bet I can,” said the liquor expert. And finally they put up a substantial wager on the outcome of the dispute, which was conditioned about like this: The liquor expert was to distinguish between three kinds of liquor and name the brand of each. He was to drink the liquor blindfolded, and was to have the privilege of selecting the three kinds of whisky to be used in the test. He selected a well-known brand of rye whisky and an equally well-known brand of bourbon, both being case goods, and as the third grade he picked the bar liquor dispensed in the place. He was blindfolded and the bartender poured out a drink of each of the whiskies and placed them upon the bar. The expert picked up the first glass and applied it to his nose, then tipped it skyward and drained it. “That was the case bourbon,” he said. The next glass was correctly pronounced to be the bar whisky and the final drink, of course, was the case rye. He won his bet and the tea man had to own that he was beaten. The money was paid and the tea man turned to the liquor man and said: “How on earth did you do it?” “Just as simple as shooting fish in a barrel,” said the lucky winner. “You see, it is not very difficult to distinguish between rye and bourbon, if you have not been drinking,” he explained. “The taste and the smell of the two varieties is distinctive, and even a novice can tell them apart. Now I realize as well as my friend from New York that after taking two drinks no man on earth can tell one kind from the other with enough certainty to name the brands. You see, I rather took advantage of him when I claimed that I could tell more than two brands and we settled upon three. For if I could tell the two first drinks I took the other one must of necessity be the third, and so it is as easy to tell three kinds as it is two.

“How did I do it? Well, I do not care if you know, now that the bet has been decided. As I said before, the difference between rye and bourbon whisky is enough to announce itself to anyone who is at all familiar with liquor, provided he has not been drinking immediately before the test. Now you noticed that I picked out a case rye and bourbon, and the liquor served over this bar is also rye. Now the difference between the bar rye and the case bourbon would be easy enough to distinguish, but a person would naturally think that if I had to pick between two rye whiskies I would have been ‘up against it.’ Well, I took that chance, because it is against ethics to wager money on any proposition where the other fellow hasn’t a chance. But when all is said and done I did not run any desperate risk. The reason I was so certain of my ability to pick out the three brands lay in the fact that I noticed that the bar whisky was kept on the ice all the time, while the case goods came from back of the counter, and the liquor contained in the bottles on the shelves was considerably higher in temperature than that contained in the rye whisky dispensed over the bar. I have been around enough to know the difference between rye and bourbon, and when I smelled of the first glass of liquor and found that it was bourbon, I knew from my sense of smell alone that it must be case bourbon because the other varieties selected for the test were rye liquor. The second glass did not present any difficulty either, for my sense of touch told me that the glass was 20 degrees colder than the one I had just set down, and must of necessity be the bar whisky. The rest, of course, was easy. Simple, wasn’t it? Just as easy. No trouble at all. Like finding our friend’s money on the street.” The whisky expert turned to pass out of the barroom to the hotel lobby, when the tea man called to him and asked him a question in a low tone of voice. “What?” asked the astonished liquor man. “Why of course I can’t now. I could not tell the difference between champagne and mineral water, nor could any other man in my situation.”