[A humble request: If you can, please donate to help me carry on tracing word histories. Thank you.]

Of British-English origin, the slang noun cakehole designates a person’s mouth.

—U.S. synonym: piehole.

The noun cakehole occurs, for example, in the column Watts’ Happenings, by Steve Watts, published in the White County Citizen (Searcy, Arkansas, USA) of Friday 18th July 2025 [page B9, column 4]:

I had pretty much known about the principle of fasting since I was young because it was encouraged during biblical times, but the scriptural focus was on spiritual purposes, such as devoting time to prayer and studying. (Apparently, if you’re not cramming stuff in your cakehole all day, you have time to stuff more important things into your mind.)

These are, in chronological order, the earliest occurrences of cakehole that I have found—this noun seems to have originated in British-Army slang during the First World War (1914-18):

1-: From the Stockport County Borough Express and Advertisers’ Record (Stockport, Cheshire, England) of Thursday 7th September 1916 [page 3, column 4]:

“EXPRESS” CHUMS AT THE FRONT.

SURPRISE MEETING IN A DUG-OUT.A former apprentice from the Express Office writing from France on Sunday week to a member of the staff observes:—Just a few lines to let you know I’m in the pink and still batting. I had a visit from another of our apprentices a few nights ago. I had been out, and landed back for tea about 7-30. When I entered our dug-out, who should be perched on the bed but Teddy W——. There was the usual old smile on his counting-house and the inevitable Woodbine stuck in his cake-hole. Comprez “cake-hole?” Of course we had a good long jaw, and settled the war several times over, and then decided on the future of the present campaign; but somehow or other the war is still on. Ted had come near where we were to go into hospital with a slight skin disease. He is not bad, but has to be watched, to notice the progress made.

2-: From Service Slang: A First Selection (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1943), a dictionary of slang used in the British Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force, by John Leslie Hunt and Alan George Pringle [page 20]—as quoted in the Oxford English Dictionary (current online edition):

Cake hole, the airman’s name for his or anyone else’s mouth.

3-: From the column From a Window In Fleet Street. Written in the Journal’s London Bureau, dated London, 20th March 1945, published in The Journal (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) of Friday 6th April 1945 [page 8, column 4]—the reference is to A Dictionary of R.A.F. Slang (London: Michael Joseph Ltd, 1945), by the New Zealand-born British lexicographer Eric Honeywood Partridge (1894-1979):

Mr. Eric Partridge has compiled a Dictionary of R.A.F. Slang. Every war that lasts any considerable time produces its crop of combatant slang, but until the 1914-18 affair no serious attempt was made to preserve a record. A good deal of last war’s service slang still survives, and is used by present-day warriors, but it has been richly augmented during this war, and particularly by our gallant airmen.

The Royal Navy has always referred to the sea as “the drink”, but the R.A.F. distinguishes between oceans. The Atlantic is “the Gravy”, and the North Sea “the Juice”. Even civilians now use “browned off”, which is a service phrase, but in the R.A.F. both “brassed off” and “cheesed off” mean about the same thing. Our airmen refer to a machine gun as a “chatterbox”, to machine-gun fire as “confetti”, both of which are excellent; to a chestful of ribbons as a “fruit salad”, to a mouth as a “cake-hole”, and to a tail-landing in which the undercarriage fails to drop as “praying mantis”.

If anyone crashes, the R.A.F. phrase is “Newton got him”, which is, of course, an allusion to the discoverer of gravitation.

4-: From The Island Forbidden To Man (London: Hodder and Stoughton Limited, 1946), by the British novelist Muriel Hine (1874-1949) [chapter 16, page 304]:

She refilled his cup. “Sugar?”

“What a memory! One lump, please.” Piers passed her a bun. “Put that in your cake-hole. The nicest one I’ve ever kissed!”

5-: From The Epicures, a short story by T. Thompson, published in The Manchester Guardian (Manchester, Lancashire, England) of Monday 15th December 1947 [page 3, column 6]:

“Hoo says hoo doesn’t know how folks cleaned up afore vacuums come in.”

“Tha’rt arguin’ on false premises,” said Young Winterburn. “Tha has to get a tin full o’ nowt afore tha con put summat in it.”

“Shut thi cake-hole,” said Owd Thatcher. “How con tha get summat full o’ nowt?”

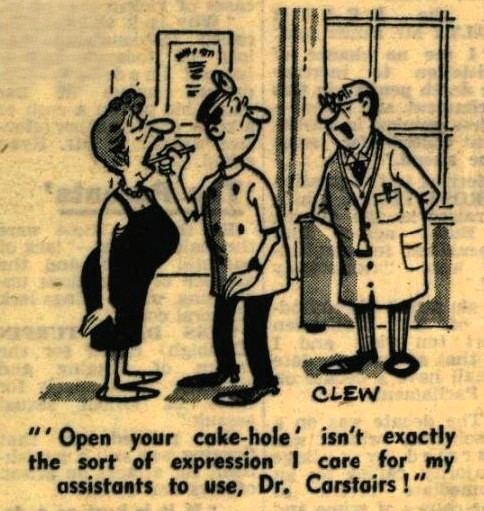

6-: From the caption to the following cartoon, published in the Daily Mirror (London, England) of Friday 10th October 1958 [page 6, column 4]:

“‘Open your cake-hole’ isn’t exactly the sort of expression I care for my assistants to use, Dr. Carstairs!”

7-: From The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (Oxford University Press, 1959), by the English folklorists Iona Opie (1923-2017) and Peter Opie (1918-1982) [chapter 10: Unpopular Children: Jeers and Torments, page 194]:

If a child has no authority for obtaining quiet he can seek it by brute force, by verbal force, or by guile. Verbal force can be very persuasive. […] ‘Put your head in a bucket of water three times and bring it out twice’ (said ‘particularly to persons one dislikes’), ‘QUIET!’ ‘Quit the racket’, ‘Shsss!’, ‘Sharrap!’, ‘Shut your cake-hole’, ‘Shut your chops’, ‘Shut yer face’—‘fizzog’—‘flycatcher’—or, ‘gate’ (‘gate’ is surprisingly common).