Twelfth Day denotes the twelfth day after Christmas, i.e. 6th January, on which the festival of the Epiphany is celebrated, and which was formerly observed as the closing day of the Christmas festivities.

(Epiphany denotes the festival commemorating the manifestation of Christ to the Gentiles in the persons of the Magi; via Old-French and Anglo-Norman forms such as epyphane (Modern French épiphanie) and ecclesiastical Latin epiphania, this word is from Greek ἐπιϕάνια (= epiphánia), from the verb ἐπιϕαίνειν (= epiphaínein), meaning to show forth, manifest.)

Twelfth Night denotes the evening before Twelfth Day, formerly observed as a time of merry-making. Twelfth Night, Or what you will is the title of a comedy by the English poet and playwright William Shakespeare (1564-1616), believed to have been written around 1601-02 as a Twelfth Night’s entertainment for the close of the Christmas season. In Shakspeare and his Times (London, 1817), Nathan Drake (1766-1836), English essayist and physician, explained:

Shakspeare has given the appellation of Twelfth Night to one of his best and most finished plays. No reason for this choice is discoverable in the drama itself, and from its adjunctive title of What You Will, it is probable, that the name was meant to be no otherwise appropriate than as designating an evening on which dramatic mirth and recreation were, by custom, peculiarly expected and always acceptable.

Twelfth cake, short for Twelfth-night cake, or Twelfth-tide cake, denotes a large cake used at the festivities of Twelfth Night, usually frosted and otherwise ornamented, and with a bean or coin introduced to determine the ‘king’ or ‘queen’ of the feast. In Observations on Popular Antiquities (Newcastle upon Tyne, 1777), John Brand (1744-1806), English antiquarian and Church of England clergyman, gathered “the present Manner of drawing King and Queen on this Day [i.e. the Epiphany], from an ingenious Letter preserved in the Universal Magazine, 1774”:

“I went to a Friend’s House in the Country to partake of some of those innocent Pleasures that constitute a merry Christmas; I did not return till I had been present at drawing King and Queen, and eaten a Slice of the twelfth Cake, made by the fair Hands of my good Friend’s Consort. After Tea Yesterday, a noble Cake was produced, and two Bowls, containing the fortunate Chances for the different Sexes. Our Host filled up the Tickets; the whole Company, except the King and Queen, were to be Ministers of State, Maids of Honour, or Ladies of the Bedchamber.

“Our kind Host and Hostess, whether by Design or Accident became King and Queen. According to twelfth Day Law, each Party is to support their Character till Midnight. After Supper one called for a King’s Speech, &c.”

John Brand also wrote:

The Twelfth-Day it self is one of the greatest of the Twelve, and of more jovial Observation than the others, for the visiting of Friends and Christmas-Gambols. The Rites of this Day are different in divers Places, tho’ the End of them is much the same in all; namely, to do Honour to the Memory of the Eastern Magi, whom they suppose to have been Kings. In France, one of the Courtiers is chosen King, whom the King himself, and the other Nobles, attend at an Entertainment. In Germany, they observe the same Thing on this Day in Academies and Cities, where the Students and Citizens create one of themselves King, and provide a Magnificent Banquet for him, and give him the Attendance of a King, or a stranger Guest. Now this is answerable to that Custom of the Saturnalia, of Masters making Banquets for their Servants, and waiting on them; and no doubt this Custom has in Part sprung from that.

At Epiphany, it is still traditional for French people to get together and share une galette des rois, a round, flat pastry filled with frangipane (almond paste). A small figurine is baked inside the pastry, and the person who finds it in his or her portion is given a cardboard crown to wear. This small object, now made of porcelain or plastic, used to be a broad bean, whence its name, la fève. The tradition is known as tirer les rois, to draw the kings. In some families, a child goes under the table while the pastry is being shared out and says who should receive each portion.

At the palais de l’Élysée, the President of the French Republic also observes this tradition, but there is no fève in the pastry, as protocol forbids the President from being crowned, even for one day.

William Hone (1780-1842), English author, satirist and bookseller, described the contemporary London customs in The Every-day Book; or, Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements, Sports, Pastimes, Ceremonies, Manners, Customs, and Events, Incident to Each of the Three Hundred and Sixty-Five Days, in Past and Present Times (London, 1826):

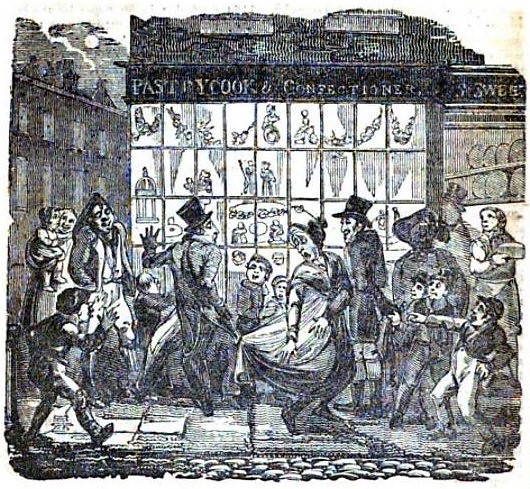

In London, with every pastrycook in the city, and at the west end of the town, it is “high change” on Twelfth-day. From the taking down of the shutters in the morning, he, and his men, with additional assistants, male and female, are fully occupied by attending to the dressing out of the window, executing orders of the day before, receiving fresh ones, or supplying the wants of chance customers. Before dusk the important arrangement of the window is completed. Then the gas is turned on, with supernumerary argand-lamps and manifold wax-lights, to illuminate countless cakes of all prices and dimensions, that stand in rows and piles on the counters and sideboards, and in the windows. The richest in flavour and heaviest in weight and price are placed on large and massy salvers; one, enormously superior to the rest in size, is the chief object of curiosity; and all are decorated with all imaginable images of things animate and inanimate. Stars, castles, kings, cottages, dragons, trees, fish, palaces, cats, dogs, churches, lions, milkmaids, knights, serpents, and innumerable other forms in snow-white confectionary, painted with variegated colours, glitter by “excess of light” from mirrors against the walls festooned with artificial “wonders of Flora.” […]

[…] On Twelfth-night in London, boys assemble round the inviting shops of the pastrycooks, and dexterously nail the coat-tails of spectators, who venture near enough, to the bottoms of the window frames; or pin them together strongly by their clothes. Sometimes eight or ten persons find themselves thus connected. The dexterity and force of the nail driving is so quick and sure, that a single blow seldom fails of doing the business effectually. Withdrawal of the nail without a proper instrument is out of the question; and, consequently, the person nailed must either leave part of his coat, as a cognizance of his attachment, or quit the spot with a hole in it. At every nailing and pinning shouts of laughter arise from the perpetrators and the spectators. Yet it often happens to one who turns and smiles at the duress of another, that he also finds himself nailed. Efforts at extrication increase mirth, nor is the presence of a constable, who is usually employed to attend and preserve free “ingress, egress, and regress,” sufficiently awful to deter the offenders.

The British caricaturist and book illustrator George Cruikshank (1792-1878) depicted boys ‘nailing’ spectators’ coat-tails outside a pastry cook’s shop specially for The Every-day Book of 1826: