The noun Franglais is a blend of the French words français and anglais. Since the First World War, it has independently been coined on several occasions in order to denote various realities.

As a derogatory name for French speech that makes excessive use of English words and expressions, Franglais seems to have been coined by the French teacher, grammarian, translator and author Maurice Rat (1893-1969). According to the French essayist and novelist René Étiemble (1909-2002), who popularised the term in Parlez-vous franglais ? (Paris, 1964), Maurice Rat wrote the following in his column Potins de la grammaire (Grammar Tattle) published in the newspaper France-Soir on 26th September 1959:

Français ou franglais ?

L’élite des Argentins écrit et parle un français mêlé d’espagnol que le spirituel chroniqueur du Quotidien, le grand journal français de Buenos Aires, a proposé de baptiser le fragnol*. Faudra-t-il appeler bientôt franglais ce français émaillé de vocables britanniques que la mode actuelle nous impose ?

translation:

The Argentine elite write and speak a French mixed with Spanish that the witty columnist of the Quotidien, the leading French newspaper in Buenos Aires, has proposed to christen fragnol*. Shall we soon have to call Franglais this French peppered with British terms that the present fashion imposes on us?

(* fragnol: a blend of français and espagnol)

Paul Ghali, reporting from Paris, evoked Étiemble in Intellectual Revolution: Parisians Learning a New Language—Franglais, published in The Philadelphia Inquirer of 11th December 1962:

A Sorbonne professor, René Étiemble, is fighting what he calls a new form of “subversion” in France—the mass invasion of Anglo-American verbs, nouns, adjectives and expressions.

“There won’t be any French language left in 40 years,” said Étiemble. “We’ll then be speaking a sort of gibberish that I call Franglais.” (A contraction of the French words “Français” and “Anglais”).

To prove his point, Étiemble has assembled some 5000 English or English-sounding words and phrases currently used by the French. “When you think that most men know less than 3000 words, you can imagine the threat Franglais is,” he declared.

Prof. Étiemble goes through the day of an average Frenchman to show that as soon as he arises he uses Franglais—donning his pullover and patting his pre-electric shave on his face. Then he goes to his business where he meets his boss and his pals until he takes off to lunch at the corner snack-bar or cafeteria where he downs a pick-me-up or a gin-fizz or a whisky.

Meanwhile, the man’s problem child slips out of his nursery while his babysitter is not around. The older boy drives in the family hardtop to a night club with his baby-doll.

This is an example of the jargon which makes Étiemble shudder. All the English words cited above appear in a short story written by Étiemble in Franglais.

The professor does not believe that the addition of English words enriches the French language. “On the contrary,” he says, “it impoverishes it by knocking out perfectly good French words or by destroying nuances.”

But, in the sense of Canadian French that contains a significant quantity of English words and phrases, Franglais is probably an independent coinage, since it had already been used in an article about Quebec published in the Alexandria Daily Town Talk (Alexandria, Louisiana) on 7th September 1962:

Assailed by English-language media, politically thwarted by Ottawa, and forced to hear the continuing deterioration of spoken French into a mixture of French and English (Franglais), the reaction of many French-Canadian students and intellectuals has been to adopt separatism as a last desperate attempt to stop the rot.

In any case, Franglais had been coined during the First World War in the sense of unidiomatic French spoken by an Anglophone. The earliest instance that I have found is from Red Cross News Notes, published in the Williston Graphic (Williston, North Dakota) on 9th May 1918:

“Franglais” is a new language that you hear in France today. The word is made of “francais” [sic] and “anglais”—the French words for French and English—and the language itself is made out of a fearful jumble of words that were perfectly good when they played by themselves but don’t always mix.

Franglais is what you hear where American and English men and women without a very good knowledge of their hosts’ own speech find themselves at work alongside of Frenchmen and Frenchwomen—soldiers, nurses, relief workers, shopkeepers and all sorts of folks.

American Red Cross workers say that when you gather up several hundred little French babies who have hardly begun to speak any language at all, and several hundred littler ones who are speaking the universal and universally incomprehensible language of babyhood, the results are one degree harder to understand than grown-up Franglais.

But somehow the French babies and their American caretakers get on just wonderfully together.

The word seems to have been independently coined again in, or more probably before, 1960 in the sense of unidiomatic English spoken by a Cajun. In his column Off the Cuff, published in the Daily World (Opelousas, Louisiana) on 12th January of that year, R. J. Reed made a distinction between Frenglish and Franglais:

Frenglish or Franclais [sic]?

According to the French department at Southwestern Louisiana Institute, the majority of our French-acadian descendants speak a jambalaya of French and English or English and French, depending on which language was first learned on Mama’s knee or Daddy’s shoulders.

The results are varied, colorful and confusing. From a bi-linguist, it’s both expressive and varied; since all you have to do is switch from French to English when the expression or vocabulary is not too clear in one or the other. To a mono-linguist, this calls for possible local color, but a lot of confusion; to an out-of-state visitor, total confusion, suspician [sic] and possible frustration.

You’ll hear, for example, a high-powered salesman telling his half-listening prospect:

“Allon dire ca prend a half million bucks to run a company comme ca ici. . .

“. . . en autre not, if we don’t run into some malchance, we should do bien, ehn?”

Or, “C’est pas comme another company qui commence with $250,000. . . Tu wa, we made $10,000 claire last year, mais that’s not enough. . . Allons dire ca prend a half million. . . Non, non, cher, not that way. . . La, let’s see how much that is. . . Eh, garcon, if we only knew!” etc. . .

The above was an actual dialogue in Frenglish, copied almost word for word by this column. It could be called Frenglish, because the English dominates the French. And a conversation of this sort can be followed fairly well by an English-speaking audience.

But take the Franglais now. Yes, take it! It takes a real French-English background to follow this jargon, colorful or expressive though it may be. It can easily be distinguished from Frenglish, because even the English in Franglais is not only idiomatic as all get-out, but it is also a direct translation from French to English. To avoid any more confusion, here are some real samples garnered over the past decade.

“We have a nice fresh (breeze) outside today, yes? J’crois I’ll go get me a big pound of fresh cochon (pork) and make me some grillade amarinees (pickled and peppered beef) pour diner.”

“Say, do you have any ruban bleu (blue Ribbon) at your store, the kind pour match ma robe (dress) I bought there last summer?”

“I defend (defy) any of you to tell that to my figure (face).”

“We sure forced (hoped) the bus would have a flat so we wouldn’t have to go to school today.”

“I blistered (wounded or winged) three ducks and killed two.”

“I planted (stuck) an echappe (splinter) in my foot.”

“And when my bunch of geese came back the other day there wasn’t one left.”

“Wait here till I throw my cow over the fence some hay.”

“Mago save my books?”

In this advertisement for Unity Barnes, from The Tatler (London) of 8th September 1965, Franglais is, again, likely to be an independent coinage:

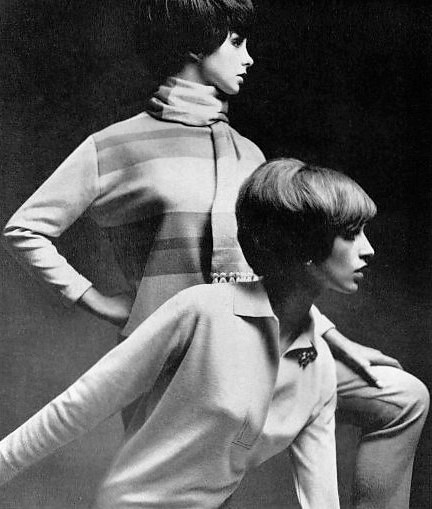

This is a story of colours that co-ordinate, separates that inter-mix, sizes that don’t matter because everything can be made to measure. In front, a shirt-necked sweater and skirt in creamy beige wool Racine jersey, top 14 gns., skirt, 16 gns. Behind, a long sweater in the same beige, boldly striped in hot pink and blue, 16 gns., with an outsize fringed muffler, 13 gns. All from stock or to order (at the same price) from Le Style Franglais, 25 Lowndes Street, S.W.1

photograph from the advertisement for Unity Barnes – The Tatler – 8th September 1965