[A humble request: If you can, please donate to help me carry on tracing word histories. Thank you.]

The phrase seven years’ bad luck (also seven years’ ill luck, seven years of bad luck and seven years of ill luck) designates a period of bad luck superstitiously believed to be the consequence of breaking a mirror or, occasionally, of another action or incident.

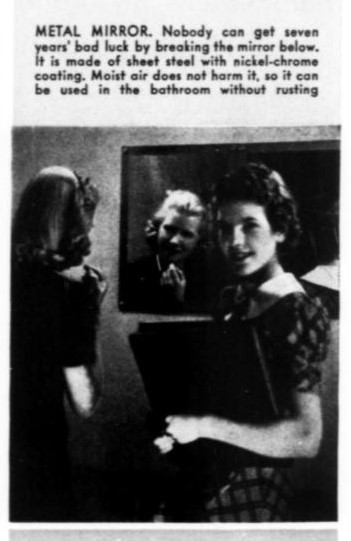

This phrase occurs, for example, in the caption to the following photograph from Appliances for the Household, published in Popular Science Monthly (New York City, New York, USA) of January 1941 [page 120, column 2]:

METAL MIRROR. Nobody can get seven years’ bad luck by breaking the mirror below. It is made of sheet steel with nickel-chrome coating. Moist air does not harm it, so it can be used in the bathroom without rusting

The specific—and unexplained—seven-year period of bad luck seems to have first been mentioned in the early 19th century [cf., below, quotations 1, 2 & 3], but the idea that breaking a mirror brings bad luck seems to date back to the late 18th century. The earliest occurrences that I have found are as follows:

a) From Observations on Popular Antiquities: Including the whole of Mr. Bourne’s Antiquitates Vulgares, With Addenda to every Chapter of that Work: As also, An Appendix, Containing such Articles on the Subject, as have been omitted by that Author (Newcastle upon Tyne: Printed by T. Saint, for J. Johnson, London, 1777), by the British antiquarian John Brand (1744-1806) [Observations on Chapter IX., page 91]:

The breaking a Looking Glass is accounted a very unlucky Accident.—Mirrors were formerly used by Magicians in their superstitious and diabolical Operations; and there was an antient Kind of Divination by the Looking Glass: * Hence it should seem the present popular Notion.

b) From A Provincial Glossary, with a Collection of Local Proverbs, and Popular Superstitions (London: Printed for S. Hooper, 1787), by the British antiquary and lexicographer Francis Grose (1731-1791) [Superstitions: Omens portending Death, page 48]:

Breaking a looking-glass betokens a mortality in the family, commonly the master.

These are, in chronological order, the earliest occurrences that I have found of the phrase seven years’ bad luck (also seven years’ ill luck, seven years of bad luck and seven years of ill luck):

1-: From Signs and Sayings, a letter to the Editor by ‘Anti-Augurism’, published in The Scourge; Or, Monthly Expositor of Imposture and Folly (London, England) of Wednesday 1st December 1813 [page 461]:

There is no disputing with custom, or in other words, with prejudice. We are not far behind Rome, in her chalk and charcoal days (lucky and unlucky) ominous signs, and proverbial sayings. A short time since I was staying in Euphemia’s house, who has two fine daughters, and as accomplished as a modern seminary can make them; but it seems, a superior education cannot erase the idle impressions early inculcated by a superstitious parent: not to occupy more of your time than is necessary, I shall mention a few trifling incidents, which elated or depressed my friend’s little family. The morning I called on my friend I found her youngest daughter, Caroline Cleopatra Constantia, in tears; and asking the occasion of so much grief, her mother told me, in a most serious tone, that poor Caroline Cleopatra Constantia had had the misfortune to break a looking glass, which foreboded seven years ill-luck—before I had time to ridicule such folly, Georgiana Maria Delphina came running into the room, acquainting her mother that she had tumbled up stairs; thank Heaven! ejaculated the silly parent, this is a good sign, for you will be shortly married. At dinner-time, the salt was spilt, and clouded the brow of my hostess, as an omen of sorrow; but a round cinder dropping from the grate, brought smiles on her countenance, as it was a sign of a full purse; this sunshine lasted but a little while, for an oblong one popping out of the fire, represented a coffin, and that was a sure sign of death.

2-: From Specimens of an intended Irish Newspaper. The “Pat Bull.”—By Louisa H. Sheridan, by the British author and illustrator Louisa Henrietta Sheridan (1810-1841), published in the Westmorland Gazette, and Kendal Advertiser (Kendal, Westmorland, England) of Saturday 27th October 1832 [page 4, column 4]:

On Tuesday Michael O’Rafferty was brought before a magistrate, charged by several persons with maliciously firing at and breaking a number of looking-glasses, with intent to bring ‘seven years of ill-luck’ to their owners. The prisoner, who was of the ‘faded genteel’ order, seemed deeply affected, as far as glimpses of his countenance were obtained through the holes in his pocket handkerchief; and he vehemently denied having committed the acts with intent to bring evil on unoffending people. He stated that he was the rejected son of a noble, and being totally destitute of the means of subsistence, he had come to the fearful resolution of putting a violent end to his woes. Determined that the rash act should be effective, he had borrowed pistols, and, in order to make sure of his mark (being a bad shot) had practised shooting at his own resemblance in the mirrors, which, unfortunately, were broken by these experiments of suicide. The magistrate now declared that the affair had taken a more serious aspect, and he felt bound to commit the prisoner to stand his trial for ‘shooting with intent to kill.’

3-: From My Godmother’s Omens, a short story by Georgina Smith, published in The New Monthly Belle Assemblée (London, England) of Sunday 1st November 1835 [page 228, column 1]:

From this moment I was an undoubted favourite, yet what perhaps tended more than all the rest to establish my supremacy, was the fact, of Mrs. Barbara’s having broken a looking-glass during our absence. This unfortunate event, Mrs. Troublewit assured me invariably entailed seven years ill-luck on the offender. “I was certain something unpleasant would occur,” she exclaimed, “for I was annoyed the whole of yesterday with the itching of my nose, a plain proof I should be vexed; again, the salt was spilt; and thirdly, the loaf separated the very instant I touched it, an infallible sign of a parting in the family.”