Apparently of Irish-English origin, the phrase away with the fairies means giving the impression of being mad, distracted, or in a dreamworld.

The earliest instance that I have found is from the account of a trial at Ardee petty sessions, published in The Drogheda Argus, and Leinster Journal (Drogheda, County Louth, Ireland) of Saturday 10th August 1907; Mr S. H. Moynagh, solicitor, is questioning one of the witnesses, Patrick James Osborne, who pretends to know nothing regarding the case:

[Witness said] He didn’t know Mathews at all.

Mr Moynagh—Do you regard him as an enemy?

Witness—I never heard of him until a week ago.

Mr Moynagh—What age are you?

Witness said he was 17, but he never heard anything about this farm until a

short time ago.

Mr Moynagh—Where were you? Were you away with the fairies or what? (laughter).

This phrase ultimately refers to the belief that the fairies spirit away human beings, as exemplified by an Irish murder case of 1909.

On Tuesday 23rd February of that year, at a special Court held at Galway, two brothers, Michael and Bartley Coyne, were charged with the wilful murder of James Bailey at Lettermore, County Galway, on Tuesday 2nd February.

Accounts of that trial appeared in many Irish and English newspapers the following day, Wednesday 24th February 1909; for example, The Bolton Evening News (Bolton, Lancashire) reported that the victim’s father and sister declared that the following had happened immediately after the murder:

Bailey’s father stated that when he came on the scene Michael Coyne said to him: “Don’t mind your son; that is not him you see there. He is gone away, and I know well he is gone away.” Bridget Bailey said that Michael had made the same remark to her, by which she understood that he meant that her brother was away with the fairies, and that it was not he who was lying there.

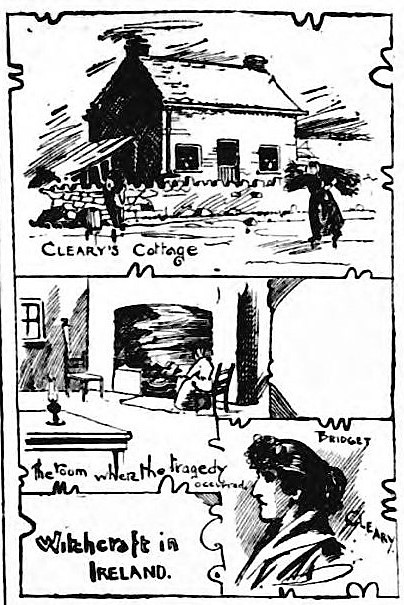

That superstition had previously led to an abominable murder. In March 1895, at Ballyvadlea, near Clonmel, County Tipperary, Bridget Cleary died from burning and other ill-treatment inflicted by her husband, father, cousins and several other persons, who believed that she had been spirited away by the fairies; the following account and illustration are from The Beverley Recorder and General Advertiser (Beverley, Yorkshire) of Saturday 6th April 1895:

THE WITCH BURNING CASE

The extraordinary charge against five men belonging to Ballyvadlea, near Clonmel, having wilfully murdered Bridget Cleary, the wife of one of them, under the supposition that she was a witch, has been further investigated before the Clonmel justices. Evidence was given to the effect that the woman was placed on the fire and held there by the prisoners. The story of the terrible occurrence is thus summed up by a Clonmel correspondent. Bridget Cleary, the victim, was a handsome, well-favoured young woman of medium height, fresh complexion, with very dark wavy hair, beautiful eyes, and pleasing expression. She was 26 years old, and had been married to the prisoner, Michael Cleary, about eight years. She had no children, and her father, Patrick Boland, lived in the same cottage. Husband, wife, and father-in-law are said to have lived on excellent terms until a short while ago, when Bridget is believed to have had an attack of influenza, causing her to suffer from hallucinations. The husband, so we are told, forthwith went to consult a “fairy doctor,” and it was pronounced that the real Bridget Cleary had been stolen away by the fairies, and that an evil spirit possessed her body. On the night of the 14th ult., according to the evidence given at the magisterial and the coroner’s hearing of the case, the first series of “remedial” measures—better described as brutal assaults—was taken. Herbs were administered, a disgusting decoction of indescribable filth was poured over her body and forced into her mouth, four men holding her down on the bed, a red-hot iron being used to make her open her mouth, and her throat severely gripped to make her swallow. She was then dragged into the next room, and held with her naked flesh pressed on to the bars of the hot grate. While there she was made to repeat her own name and that of her husband three times, certain incantations were said, and she was then put back to bed. It was thought by torturing the body to exorcise the evil spirit and bring back Bridget’s “own self” again. It is hardly surprising that the wretched woman was raving all next day, and stronger measures had to be resorted to that night. What the victim suffered ere death relieved her no tongue can tell.

A letter published in The Morning Post (London) of Tuesday 9th April 1895 explained the cultural background to Bridget Cleary’s murder (this letter also helps to understand the above-mentioned assertions made by Michael Coyne):

The magisterial inquiry now proceeding at Clonmel, Tipperary, concerning the Cloncur “witch” burning and for which, pending official examination, ten persons are in custody, brings a prevalent superstition vividly before the public, and in justice to the miserable beings implicated it seems only right that the positive fact of the widespread acceptance of this particular superstition should be made equally public. The belief firmly rooted and acted upon is that in certain cases a “ghost” (such is the Connemara term), “witch,” or “fairy” takes the form and semblance of the sick, or it may be dead person, the real person having been spirited away by the fairies. Why such a change is worked is not accounted for, nor do the people attempt to reason or explain; they simply accept the transubstantiation and believe. A person is ill, or dies suddenly. Some one says the fairies have taken him or her; so the body, alive or dead, visible and present, is not the real body, but a personification substituted by the fairies and possessed by a “witch” or “ghost,” and as such is sometimes, as in Connemara, carefully tended lest the fairies should revenge themselves upon the real person, then in their power, or, as in the Tipperary case, an attempt is made to exorcise the “witch.” How often such attempts end fatally and never become public it would be hard to say. The clergy are kept in ignorance of the immediate or individual case, though it is impossible to credit that they are equally ignorant regarding the existence of the superstition. A Catholic priest may even be called in to administer the last sacraments, yet be left in perfect ignorance of the fact that every word or action in the Holy office is eagerly watched, as a test to confirm or dissipate the superstition, the onlookers hoping the “witch” will in some way betray its presence. Again, the sufferer, who is as firmly imbued with the superstition as the watchers, and is moreover weakned [sic] by illness, or possibly in a semi-delirious condition, often acts in a manner which confirms the worst fears and establishes the belief.