The noun bobby is an informal British name for a police officer.

It is from Bobby, diminutive of Bob, pet form of Robert, in allusion to the name of Robert Peel (1788-1850), British Conservative statesman. British and Irish newspapers often referred to him as Bobby Peel; for example, on 21st November 1829, The Drogheda Journal; or, Meath & Louth Advertiser (Drogheda, County Lough, Ireland) published a “fashionable alphabet” containing:

[…]

I Washington Irving¹, the new Yankee Sec

[…]

O Dan O’Connell², the mob rhetorician

P Bobby Peel, the police politician

[…]

Z any great man, who’s a very great bore.

¹ Washington Irving (1783-1859), American author, was at that time Secretary to the American legation in London.

² Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847) was an Irish nationalist leader and social reformer.

As Home Secretary, Robert Peel established the Metropolitan Police: the British Parliament website explains the following about An Act for improving the Police in and near the Metropolis, known as the Metropolitan Police Act, which was passed in 1829:

The issues of crime and policing were taken up by Robert Peel when he became Home Secretary in 1822. Peel and his ministerial colleagues saw the increase in criminal activity as a threat to the stability of society.

Metropolitan Police Bill

In 1828, another Commons inquiry reported in favour of a police force for London, and in 1829 Peel’s Metropolitan Police Bill received parliamentary approval.

The new Act established a full-time, professional and centrally-organised police force for the greater London area under the control of the Home Secretary. The uniformed constables embodied a new style of policing in contrast to the small and disorganised parish forces of the 18th century.

The word bobby is first recorded in the proceedings of Old Bailey, London’s Central Criminal Court, of 10th June 1844:

George Clark, Andrew Murphy, Charles Saunders, and Emma Farmer, were indicted for burglariously breaking and entering the dwelling-house of Robert Taylor, at St. Mary, Newington, about 2 o’clock in the night of the 10th of May, with intent to steal, and stealing therein, 2 bottles, value 1l.5s.; 1 neck-chain, 8s.; 1 cushion, 6d.; 17 tin checks, 4d.; 14 groats, 47 pence, 169 halfpence, and 6 farthings, his property: 2nd count, for burglariously breaking out of the said dwelling-house; and that Clark and Farmer had been before convicted of felony. […]

Benjamin Parsons (police-constable M. 107.). […] Cross-examined by Mr. O’Brien. Q. How long was it previous to seeing Murphy coming down out of the yard that you saw Farmer? A. Just before she went and gave Clark the signal—it was a signal they have got among themselves—I was not near enough to tell what it was—I heard her say something, but could not understand what it was exactly—I could not understand whether it was “a crush” or “a bobby”—I cannot swear that I heard any words of that kind—I heard her say something—it was a signal to let them know a policeman was coming.

Likewise, the noun peeler, now denoting a police officer, was originally a nickname for a member of the Peace Preservation Force, established in 1814 by Robert Peel during his term as Chief Secretary of Ireland (1812-18). The word peeler is first recorded in the proceedings of a debate that took place at the House of Commons on 27th May 1816; in response to a statement made by Robert Peel,

General Matthew said, that in consequence of the right hon. gentleman’s allusion to the county of Tipperary, of which he had the honour to be a representative, he felt it necessary to say a few words, and he would repeat, that tranquillity was restored in that county—that more had been done within a very short period through the influence of conciliation, than the right hon. gentleman’s system of police had been able to accomplish within many months, at an expense of 8,300l. to the inhabitants of the county. To pay this expense, he (general M.) as a member of the grand jury, was obliged to assent, although convinced of the inefficiency of the system. He did not, however, mean to blame the right hon. gentleman for incumbering the county with such expense, because he was aware, that the introduction of his system was called for by the magistrates; but he was fully satisfied, that more good would have been done without than with that system. Indeed, he was assured, that no good whatever was done by what, in compliment to the right hon. gentleman, were called “the peelers.” He could assure the House, that no information, as to any conspiracy or malefaction was ever obtained by those peelers—that no evil was prevented or punished through their intervention or activity. For instance, no one taken up by the peelers on the charge of being concerned in the murder of that worthy magistrate Mr. Baker, had ever been convicted, while the information which led to the apprehension and conviction of some of the murderers, was obtained by the resident magistrates. Yet the county was called upon to pay those peelers 8,300l.; that is, the innocent were compelled to pay for the guilty, while the payment made to those who contributed nothing either to the prevention or detection of guilt, in too many instances disabled tenants from paying their rent.

On 3rd May 1899, The Sketch (London) published the review of Mysteries of Police and Crime: A General Survey of Wrongdoing and its Pursuit, by Major Arthur Griffiths, review in which Tighe Hopkins wrote:

The French had a wonderful (and an atrociously tyrannous) system of police as far back as the reign of Louis XIV.; we, on the other hand, had nothing worthy of the name at the date (1830) when Sir Robert Peel “introduced a new scheme, the germ of the present admirable force.” The Duke of Wellington was at the head of the Administration; he backed Peel strongly; and—to show how little at that day we liked the idea of a regular police force—both of them were roundly abused for the measure. “The scheme of an improved police,” says Major Griffiths, “was denounced as a determination to enslave, an insidious attempt to dragoon and tyrannise over the people. . . . There were idiots who actually accused the Duke of a dark design to seize supreme power and usurp the throne; it was with this base desire that he had raised this new ‘standing army’ of drilled and uniformed policemen, under Government, and independent of local ratepayers’ control.” The “new tyrants,” the police themselves, were “raw lobsters” from their blue coats, “bobbies” and “peelers” from Sir Robert Peel, “crushers” from their “heavy-footed interference with the liberty of the subject,” “coppers” because they “copped” or captured his Majesty’s lieges.

—Cf. also the opprobrious name Jenny Darby and variants.

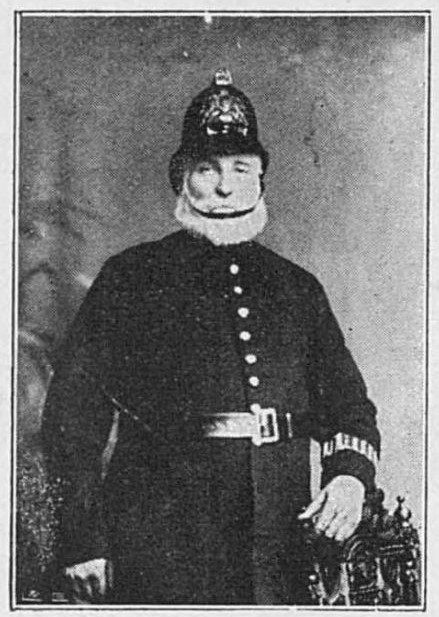

photograph of a bobby

from The Sketch (London) – 16th September 1896