A pet form of John, Johnny is used, with modifying word, to designate a person, especially a man, of the type, group, profession, etc., specified. For example:

– Onion Johnny, also Johnny Onions, was a generic name for an onion-seller from Brittany;

– Johnny Crapaud is used to personify France or the French people, or to designate a typical Frenchman;

– Johnny Arab is an offensive generic name for an Arab man;

– Johnny Foreigner is used to denote a person from a country other than those which make up the United Kingdom; and to personify people from a country other than those which make up the United Kingdom.

—Cf. also Joe Six-Pack in American English, and Joe Bloggs and Joe Soap in British English.

Likewise, from Canuck, meaning Canadian, the American-English expression Johnny Canuck is used to:

– personify the Canadian nation;

– designate Canadian people collectively.

And, as a count noun, Johnny Canuck designates a Canadian.

The earliest occurrences of the expression Johnny Canuck and variants that I have found are as follows, in chronological order:

1, 2, & 3-: From the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser (Buffalo, New York, USA):

1-: Of Wednesday 1st December 1858:

The Reciprocity Treaty and Canadian Tariff.

We are rapidly coming to the conclusion that no Yankee can be so hard-faced, or so shrewd in getting the long end of a bargain, as our Canadian neighbors. They come to us in a guise of unsophisticated innocence and wish to deal with us on the high-minded principles which govern the commercial conduct of a free Briton. They tell us they are generous to weakness, that their fraternal feeling for Brother Jonathan is so overpowering that they are willing to give up all distinctions of nationality, abolish tariffs, and have, so far as may be, free trade between the two countries. And thereupon Brother Jonathan falls in love with John Canuck, the two strike hands, and a Reciprocity Treaty results. Reciprocal affection and esteem have begotten reciprocal trade, and the brotherhood of nations becomes a fixed fact.

The sum of all this bargain is that certain enumerated articles shall be duty free on either side. Taking up the articles as we find them in the treaty, we discover that John Canuck agrees to place no tariff on cotton, coal, pitch, tar, turpentine, rice, burr and grindstones, dyestuffs, hemp and unmanufactured tobacco, these being the products of the United States which John Canuck needs, and the cheaper he gets them the better for his country. In fact, it is a question whether he would charge duty on them if there were no Treaty on the subject.

In return for this generous concession on the part of John Canuck, Brother Jonathan makes a similar slight concession. He agrees to take, without duty, the following slight list of articles: Grain, flour and breadstuffs of all kinds; fresh, smoked and salted meats; wool, seeds and vegetables; dried and undried fruits; fish of all kinds; products of fish and all other creatures living in the water; poultry, eggs, hides, furs, skins or tails undressed; stone or marble in its crude state; slate, butter, cheese, tallow, lard, brooms, manure; ores of metals of all kinds; ashes; timber and lumber of all kinds, round, hewed and sawed, unmanufactured in whole or in part; firewood; plants, shrubs and trees; pelts, wool, fish-oil; broom corn and bark, flax and tow; these being articles of which both the United States and Canada have each in abundance, which we do not export to Canada, and on which Canada therefore concedes nothing. She gains, however, the advantage of our markets, and is enabled to compete on better than equal terms with the American agriculturist.

One of the most charming features of the Treaty was the opening of a grain trade with Canada. All the wheat grown in Upper Canada was to seek a market in Buffalo, instead of going down the St. Lawrence. But it happened that Canada had a little offset to this in the privilege of navigating Lake Michigan in Canadian bottoms. Immediately after the Treaty went into effect, the Buffalo dealer found an active squad of John Canucks from Montreal in Chicago, shipping wheat down the St. Lawrence, and the diversion of the grain trade from American channels in this direction soon amounted to more than the whole exports of Canada grain proper. We gained a loss. But then we too had the precious privilege of navigating the St. Lawrence. We could send egg-shell schooners to Liverpool direct, and American bottoms might be employed in diverting trade from American channels of commerce and from American markets.

Such are the main features of the action of the Reciprocity Treaty, and we do verily believe that it has proved itself, in the light of experience, the most stupid bargain we were ever ear-wigged into—we say it with our hands on our heart in deference to the shrewdness of John Canuck.

However, a bargain is a bargain, and it is unmanly for a nation pretending to be tolerably well advanced in its eye-teeth, using the language of Watts, “to grumble and complain.” We should be willing to accept the Reciprocity Treaty, and grin and bear it till the crack of doom, if matters had only been left in the position in which they were at the conclusion of the treaty. But when the negotiations were complete, Canada set to work to adapt herself still further to her new advantages. She revised her tariff, increased the duties, rested awhile from her labors, and last winter resumed them, until she has finally put a stop to the importation of all American manufactures, with small exceptions. Our exports to Canada up to a recent date have been considerable, but under the new rules, they have decreased largely.

We will state a few illustrative instances. Boots and shoes, and other manufactures of leather have been a large item of export. The new tariff imposes on them a duty of 25 per cent, which is virtually prohibitory. Ready made clothing also pays 25 per cent. In iron manufactures we have had formerly a large trade, the export of stoves, particularly, from this point, being very large.—The duty was formerly 12½ per cent. It has been successively raised to 15 and 20 per cent, and the latter puts a quietus on the trade. The disadvantages thus inflicted on our stove manufacturers are not all seen at a glance. They pay 20 per cent duty on the Scotch pig iron employed. The Canadians pay only a trivial entry charge at Quebec. In spite of this, with our coal and system, our foundrymen were able to compete and supply Canada with stoves. But the imposition of 20 per cent Canadian duty by our reciprocal friends gives John Canuck an advantage of 45 per cent, just a little more than he needs to enable him to cast his own stoves in his own expensive way. On all drugs not used for purposes of dyeing, 15 per cent is now charged, against 5 per cent when the Treaty was made.

There is one beautiful feature of Reciprocity which we should mention here. The only country in the world where the American inventor is not permitted to take out a patent is Canada. Our affectionate cousins are so much “in the family,” that they think they have a right to the free use of American skill. A Buffalo stove inventor, for instance, gets up a new pattern at a heavy expense of time, skill and money. He patents it here, in England, France, everywhere save Canada. John Canuck comes over, buys a single stove, carries it home, takes it to pieces, files it down and begins casting from it, with his honest face glowing with delight at the small rascalities permitted him by an act of Parliament.

The amount of all this is that the Reciprocity Treaty gives all and takes nothing on the American side, and that the Canadian Tariff is expressly designed to help the Treaty. It is the sheerest humbug ever perpetrated on a too confiding people, and the sooner it is terminated by our Government, the better for all parties concerned.

2-: Of Tuesday 7th December 1858:

The Reciprocity Treaty.

A further examination into the features of the Reciprocity Treaty only shows the more conclusively, that is emphatically a bad bargain. […]

[…]

[…] Article 4 of the treaty provides that the British government may at any time suspend the right of the free navigation of the St. Lawrence “on giving due notice thereof to the government of the United States.” But no provision is made in the treaty by which the United States may suspend the right of free navigation of lake Michigan! The prudent reservation of John Canuck, by which he may at any time prevent an American bottom from unloading at Montreal, has no counterpart by which Brother Jonathan may prevent the loading of a Canadian bottom at Chicago.

3-: Of Wednesday 16th February 1859:

An International Celebration.

It is proposed by Hon. Wm. Hamilton Merritp [sic], of St Catherines [sic], C. W., that Brother Johnathan and John Canuck should unite in a common celebration of a common victory. Of late years the various deeds of arms of either nation have not been such as to induce a union in their celebration; but Mr. Merritt goes back to the

“Good old Colony times

When we lived under the king,”

and suggests that both nations should unite in the formal remembrance of the capture of Fort Niagara by the united forces of Britain and the Colonies, July 25, 1759, which broke the French domination in this part of the New World.

4-: From The Union Democrat (Manchester, New Hampshire, USA) of Tuesday 5th April 1859:

Canada Correspondence.

American Hotel, Toronto, C. W., March 28, 1859.

Editor Union Democrat:

Since my last, my peregrinations have been chiefly in what is known here as the ‘Queen’s Bush,’ a peninsula of comparatively wild land, lying between Lake Huron and Georgian Bay […].

[…]

Save Indian Corn, what can be grown in western New York can be raised successfully here. I have never seen finer samples of wheat, barley and oats, or a better yield; while all varieties of peas, without bugs—bugs don’t grow here—excel any part of the world. All esculents flourish, and are grown in enormous quantities, and with great profit, a fact which I fear New Hampshire farmers, in their fever for Black Hawks and Morgans, have nearly lost sight of. Why, Johnny Canuck would scarcely attempt to raise a family of thirteen, to say nothing of his farm stock, without some hundreds of bushels, to say the least, of the Swedish turnips or the sugar beet at hand for the winter.

5, 6 & 7-: From the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser (Buffalo, New York, USA):

5-: Of Monday 19th December 1859:

American Reciprocity.

From the Toronto Globe, Friday.Our readers are aware that the American Government have appointed a Commissioner to inquire into the effects of the Reciprocity Act, in consequence of complaints made against its working by certain interests in the United States. Mr. Hatch, of Buffalo, the commissioner, has been for some weeks at work collecting evidence, and on Wednesday he visited Hamilton for this purpose. […]

[…]

Mr. Hatch is just now the recipient of many flattering compliments from the Canadian press and people. If palaver can turn him from the position he has been understood to occupy, it will not be spared. John Canuck is the most amiable of gentlemen in matters where amiability and policy are synonyms.

6-: Of Monday 2nd April 1860:

The Reciprocity Treaty.

[…]

[…] Canada is the only civilized nation on the face of the earth which refuses the protection of a patent to a foreign inventor. The inventive genius of our country may go to France, England, or any European nation, and protect itself under their patent laws. But in Canada only, a general piracy is permitted. The stove manufacturers of Buffalo, getting up patterns at an expense of from $500 to $1,500 each, cannot rely upon any Canadian sale. They can secure no patent there, and as soon as they bring out a new and desirable invention, John Canuck comes over here, buys one stove, files it down for patterns, and three miles across the river may commence the manufacture of the same article.

7-: Of Friday 14th September 1860:

The Navigation Laws […]—[…] Mr. W. S. Lindsay […] has been sent by the British government on a special mission to Washington—its object being to induce the United States government to reciprocate the British policy of free trade in ships, and, if possible, to negotiate a treaty by which the coasting trade may be mutually thrown open to the vessels of both nations.

[…]

The above from the Montreal Herald is sublimely impudent. The proposition is to allow British bottoms to undertake the Atlantic coasting trade and to permit Canadian vessels to run between American ports upon our lakes. As it now is, they have the free navigation of Lake Michigan, but are not permitted to transact a coasting trade between any two American ports. They now propose to come in and do all our business for us, run their vessels all along the south shore of Lake Erie, derive all the profits of that rich and increasing trade, but leave it to us to maintain the labors, the custom-houses and all the expenses of government, while they escape taxation upon every dollar of their capital employed.

No, John Cannuck! We have had an overdose of reciprocity with you, and you are much more likely to witness the abrogation of your existing privileges, than to derive any new advantages from negotiation.

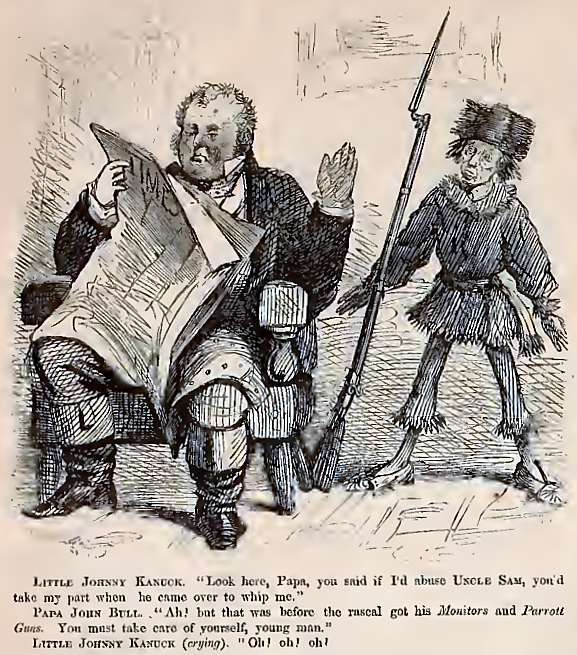

8-: From the caption to the following cartoon, published in Harper’s Weekly. A Journal of Civilization (New York City, New York, USA) of Saturday 5th July 1862:

Little Johnny Kanuck. “Look here, Papa, you said if I’d abuse Uncle Sam, you’d take my part when he came over to whip me.”

Papa John Bull. “Ah! but that was before the rascal got his Monitors and Parrott Guns. You must take care of yourself, young man.”

Little Johnny Kanuck (crying). “Oh! oh! oh!”