On Friday 28th July 1933, the Clitheroe Advertiser and Times (Clitheroe, Lancashire) published this interesting article about catchphrases in advertising campaigns:

Phrases which brought Fortunes

“Good morning! Have you ——?” How many times have you completed that quotation when jocularly saluting a friend? Perhaps you have occasionally pondered the value of such a sentence in advertising. For it is one of those phrases which have brought fortunes. Probably you can think of several others even as you read these opening lines.

It is the dream of every advertiser to strike a catch phrase—a phrase which will take the public fancy and set people talking. Something that, apart from advertisements which have to be paid for, will get into the papers as a matter of general interest. Something, if possible, that will set the public arguing about it or even quarrelling. Something that the public pretends at length is intolerable. Something, for instance, like those lines by Mark Twain in reference to regulations for omnibus conductors—

Punch, brothers, punch with care,

Punch in the presence of the passenjare. [footnote 1]

How those lines did amuse the Americans, to be sure. They spread from paper to paper, from lip to lip. They haunted the people at home, at church, at business. They were gently chanted to omnibus conductors as they sold tickets to the “passenjares.” They caused an epidemic of mild mania.S.T. 1860. X.

At all events they stuck in the public memory. That is what advertisers want—something that the public will never forget: a line about Blank’s soap which will recur to the housewife when she finds supplies run out; a phrase which will strike the man whose tummy is out of order and who wants to know of a useful pill. Mr. Morgan Richards, one of the world’s most famous advertising men, once scored a singular success with such a phrase. Advertisements occupied great spaces in the papers. They consisted of nothing but the line, in capital letters—“S. T. 1860 X.” The letters were posted on the hoardings so that they could not be missed. They were scattered broadcast by circular and handbill. They were scrawled on blank walls and gateposts. Householders received them through the post. They were painted in letters four hundred feet high on a mountain scarp, and half a forest was cut down in order that the passengers on the Pennsylvania Railroad should see them as the line passed within view of the hill.

What did those letters mean? American citizens raised discussions in ever-increasing volume. They wrote to the editors of the newspapers demanding explanations which the editors were unable to give. They made wagers, some professing to have fitting explanations. Family feuds were numerous. Wherever half a dozen people congregated together there that question would arise: What was meant by that line, S.T. 1860 X.? In due time the explanation came. Mr. Morgan Richards had projected an advertising campaign for a firm desirous of obtaining a great sale for their medicinal drink issued under the name of Plantation Bitters, and S.T. 1860 X. merely meant that the proprietor of the Plantation Bitters had Started Trading in 1860 with ten (X) dollars. And the people started in to buy Plantation Bitters right away. [footnote 2]GOOD MORNING!

“Good morning! Have you used Pears’ soap?” has passed into the ranks of phrases which are almost immortal. Mr. Barratt, to whom the advertising of the famous soap-makers owes so many of its brilliances, was one day pondering another firm’s catch-phrase. “Queer fellow, Epps,” he said to himself. “I wonder how he came to use the words, ‘Grateful and Comforting.’” It was, of course, obvious that the name and fame of the cocoa firm was largely bound up with the legend that their product was “grateful and comforting.” And so Mr. Barratt set out to discover a phrase which would similarly bind itself with the Pears’ soap. He hit upon the expedient of asking his friends to make out lists of the most popular forms of salutation. At the head of almost every one of those lists was the greeting, “Good morning!” That evidently was the best, and so the greeting and the gentle inquiry were introduced into the advertisement, with all sorts of pictorial aid, as, for instance, the picture of the sweep in his working clothes and sooty face at the door of the cottage. “Good morning, have you used Pears’ soap?” inquires the clean, bright housewife. The phrase caught on at once. Within a month or so everybody was asking the question, and the firm had one of the best advertisements in its history. [footnote 3]

WORTH A GUINEA A BOX.

Once upon a time in the market place of St. Helens, the famous glass manufacturing town of Lancashire, a man stood selling pills made according to a particular recipe of his own. He had so stood there market day after market day for months and years, doing a gradually increasing business. And to him came a countrywoman intent on buying a further supply of his medicines. “Ah, Mr. Beecham,” she said, “your pills are worth a guinea a box.” The phrase stuck. Mr. Thomas Beecham advertised and used the sentence the countrywoman had employed incidentally to express her appreciation of the pills. And business moved forward at a tremendous pace. The more it grew the more Mr. Beecham advertised. The more he advertised the more the business grew. And “Worth a guinea a box” was the sentence which found and still finds a place in the Beecham advertisements all over the world. Truly, this is a phrase which has meant fortune. [footnote 4]

There are others. We use the words, “Won’t wash clothes” in all kinds of serious and humorous connexions, but we never forget its original association with “Monkey Brand.” [footnote 5] The same may be said of the more recent but quite historic, “Alas, my poor brother,” the remarkably taking phrase which appeared with one of the most arresting pictorial advertisements which ever appeared on the hoardings or in the press. It was the forerunner of a fine series of other Bovril advertisements of scarcely less interest. [footnote 6]HE CAME!

Other phrases might be quoted, but they are not so familiar as those given, and in the nature of things there is not room for many at a time. Two good ones running simultaneously would probably have the effect of crushing each other out and destroying each other’s effect. None the less, every advertiser who knows anything about his business is only too eager to receive the inspiration which will produce a phrase to bring him fortune. He won’t be happy till he gets it, but in the meantime he does his best without it. Sometimes he endeavours to obtain his advertisement by affecting the mysterious. Entertainers, for example, are prone to putting out posters bearing the plain statement in large type that “So and So is coming.” The idea was used effectively once by a man who engaged a big hall in a town which shall be nameless, and placarded all the local hoardings with the words, “He is Coming.” And the people began to wonder who “He” might be. In a week or so the placards were altered to “He is here!” and close inspection of the placards was necessary for the people to discover that Professor So and So had arrived to give a remarkable entertainment at the local public hall, and the charges of admission were—so much. Great interest was thus evoked, and the crowd in the hall was a large one. Five minutes after the time for the beginning of the entertainment, when the audience were betraying signs of impatience, the curtain went up and revealed a stage whose only decoration was a huge white sheet bearing the words, “He has gone!” And he had gone—with all the admission money.

NOTES

Note 1: This is a reference to A Literary Nightmare, a short story by the American novelist and humorist Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens – 1835-1910), first published in The Atlantic Monthly: A Magazine of Literature, Science, Arts, and Politics (H. O. Houghton and Company – Boston and New York) of February 1876. The narrator explains that he came across “these jingling rhymes” that “took instant and entire possession” of him:

“Conductor, when you receive a fare,

Punch in the presence of the passenjare!

A blue trip slip for an eight-cent fare,

A buff trip slip for a six-cent fare,

A pink trip slip for a three-cent fare,

Punch in the presence of the passenjare!

CHORUS.

Punch, brothers! punch with care!

Punch in the presence of the passenjare!”

Note 2: This early advertisement for Drake’s Plantation Bitters was published in the Evening Star (Washington, D.C.) of Tuesday 1st April 1862:

Drake’s Plantation Bitters.

S. T. 1860 X.It invigorates, strengthens and purifies the system, is a perfect appetizer, and the most agreeable and effectual tonic in the world. It is composed of the celebrated Calisaya Bark, Roots, Herbs and pure St. Croix Rum; particularly adapted to delicate females; cures Dyspepsia and Weakness, and is just the thing for the changes of seasons.

Sold by all Grocers, Druggists, Hotels and Saloons.

P. H. Drake & Co.,

202 Broadway, New York.

Note 3: The following is an advertisement for Pears’ Soap published in The Northern Echo (Darlington, County Durham, England) of Tuesday 6th August 1889—it consists of a repetition of the slogan Good Morning! Have you used Pears’ Soap?:

Note 4: This advertisement for Beecham’s Pills was published in the Liverpool Mercury, and Lancashire, Cheshire, and General Advertiser (Liverpool, Lancashire, England) of Friday 9th September 1859:

WORTH A GUINEA A BOX.

BEECHAM’S PILLS will be found to be the best in the world for Bilious and Nervous Disorders, Sick Headache, Wind and Spasms at the Stomach, Cold Chills, Flushings of Heat, Tightness on the Chest, Difficulty of Breathing, &c. The first dose will give relief in 20 minutes.

Prepared only and sold wholesale and retail the proprietor, T. BEECHAM, Chemist, St. Helen’s, Lancashire, in boxes, at 9½d. each; post free for eleven stamps to any address, or may be ordered from any druggist.

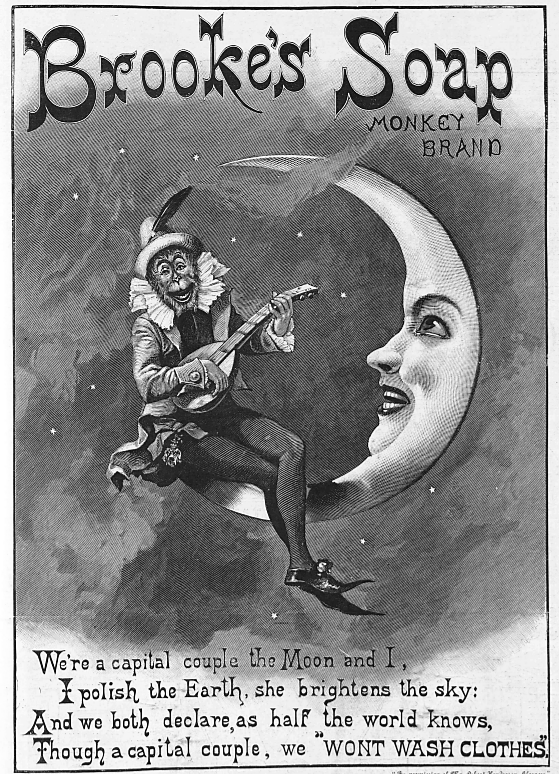

Note 5: The following is an advertisement for Brooke’s Soap Monkey Brand published in The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (London, England) of Saturday 20th December 1890—it depicts a monkey dressed as a minstrel, sitting on a crescent moon, and singing:

We’re a capital couple the Moon and I,

I polish the Earth, she brightens the sky:

And we both declare, as half the world knows,

Though a capital couple, we ”WONT [sic] WASH CLOTHES.”BROOKE’S SOAP.

MONKEY BRAND, 4D. A LARGE BAR.The World’s Most Marvellous Cleanser and Polisher.

Makes Tin like Silver, Copper like Gold, Paint like New, Windows like Crystal, Brass Ware like Mirrors, Spotless Earthenware, Crockery like Marble, Marble White.

For a thousand things in Household, Shop, Factory, and on Shipboard.SOLD BY GROCERS, IRONMONGERS, AND CHEMISTS EVERYWHERE.

Note 6: cf. origin of the catchphrase ‘Alas! my poor brother’