The phrase plain Jane, or Plain Jane, denotes a plain, dowdy, unremarkable girl or woman.

It later came to be used as an adjective meaning drab, simple, ordinary, unremarkable.

The forename Jane was probably chosen for two simple reasons: it is very common, and it rhymes with plain.

According to the earliest instances that I have found, this phrase appeared within the longer form plain (or Plain) Jane and no nonsense.

The earliest is from the Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald (Ardrossan, Ayrshire, Scotland) of Friday 30th September 1898—the phrase plain Jane and no nonsense is an attribute of the noun order, used in the sense of a type, a sort:

A NOTE TO THE LADIES.

A VISIT TO THE COMMERCIAL HOUSE, KILMARNOCK.The philosophy of clothes may appear a most unworthy study to people of the cast of mind of that old seer of Craigenputtock*, and to those who pass their days amid such stuff as dreams are made of. But to ordinary everyday people who live in a real everyday world, it is a very pretty and a very interesting study. Nay, it is a study which must be pursued very heartily if we would save ourselves from falling back into the barbarous days, and prevent our tastes from sinking into the monotony of the plain Jane and no nonsense order. Dress is a very important thing now-a-days, particularly in the ladies’ world, which world nobody, we are sure, desires to see stripped of anything that adds to its beauty.

* the seer of Craigenputtock: a nickname for the Scottish historian and political philosopher Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881), who resided at Craigenputtock, an estate in the civil parish of Dunscore, in Dumfriesshire, Scotland

The second-earliest instance that I have found is from the Newry Reporter (Newry, Down, Ireland) of Thursday 13th November 1902—the phrase Plain Jane and no nonsense is an attribute of the noun look with reference to the unattractive appearance of the interior of a building:

Newry Town Hall.

(To the Editor of the Newry Reporter.)Dear Sir.—[…] It is the opinion of any outsider I have met with that the Newry Town Hall is in a disgraceful condition. I grant that the exterior of the building is attractive, but it is at present very much in the position of the ship that was lost for want of the proverbial “halfpennyworth of tar.” One would imagine that the public pride which prompted the building of the hall would extend to seeing that it was kept up in a satisfactory manner. Then again, the stage elevation, to one who knows what a stage is, or ought to be, is absurd, and takes one all his time to imagine that it has not been designed by a “lot of old wives” of the “upper succle [= circle]” for the purpose of airing their views in a different atmosphere, and far above the heads of the “common herd.” No other reason that I know of can be given for building a stage so high that it “kricks [cricks]” the necks of the audience to look at any performance taking place thereon. One would think that Newry folks, who are “marching with the times” in many ways, would not be content to take a back seat in the matters of their “Town Hall.” I trust that this letter of mine, all imperfect though it be, will waken up some of the townspeople themselves out of their lethargy, and set them to work with a right good will to exchange the “Plain Jane and no nonsense” look of their hall, and to make the interior pleasing to the eye and a comfort to the mind (and neck).—I am, dear sir yours, &c.,

“Call a Spade a Spade.”

11th Nov., 1902.

A later occurrence of plain Jane and no nonsense is from the column Day by Day, in the Evening Telegraph and Post (Dundee, Angus, Scotland) of Monday 12th November 1917:

The master bakers of Dundee have decided not to make any more pan and French bread. So it’s plain Jane and no nonsense for us now and for the duration.

It seems that the collocation plain Jane, or Plain Jane, gained currency in the early 1900s. For example, the following is from New books and magazines, published in The Belfast News-Letter (Belfast, Antrim, Ireland) of Friday 5th July 1901:

We have also received […] the “Monthly Magazine of Fiction,” containing a novel, “Plain Jane.”

In The Era (London) of Saturday 24th October 1903, M. Witmark & Sons, “the world’s popular song publishers”, publicised their novelties for pantomime, containing, among the “dame songs”, Just Plain Jane.

This other example is from More Christmas books, published in The Daily News (London) of Wednesday 9th December 1903:

“Plain Jane” is one of Grant Richards’ “Little Dumpy Books” (1s. 6d.), and is delightfully humorous. Plain Jane is a “tell-tale tit,” and has a jolly little naughty cousin, Ann. The problem, of course, is how to teach Jane the error of her ways. She is saved through tribulation, thanks to one little bit of naughtiness in her own nature.

Finally, in its Publishers’ Column, The Scotsman (Edinburgh, Scotland) of Monday 17th October 1904 listed the following among the “books for the bairns”:

Jane. How Vain Jane Became Plain Jane. By Miss Templar. With 24 Coloured Illustrations. 32 mo, 1s. 6d.

The earliest instance of Plain Jane that I have found is from The People’s Journal (Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire, Scotland) of Saturday 11th February 1905; Plain Jane was the signature used by “a plain girl” for a letter written to “protest against Freda’s condemnation of the stylish girl”—with reference to a letter published in the same newspaper on Saturday 28th January 1905, by a woman signing herself Freda.

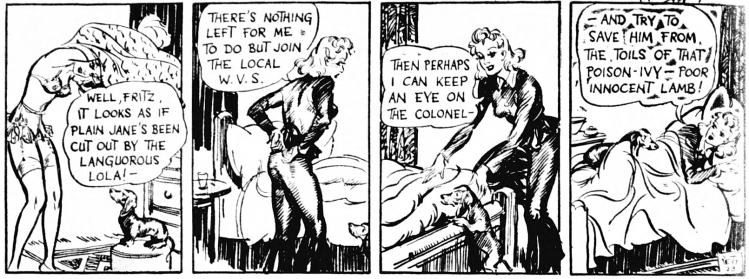

In complete contrast to the drab image reflected in the phrase plain Jane, the name Jane became famous in the 1940s as that of the beautiful and sexually alluring eponymous character of a comic strip by the English cartoonist Norman Pett (1891-1960), published in the Daily Mirror (London).

In the following, published on Friday 8th November 1940, the character paradoxically uses the phrase plain Jane about herself:

Well, Fritz, it looks as if plain Jane’s been cut out by the languorous Lola!

There’s nothing left for me to do but join the local W.V.S. [= Women’s Voluntary Service]

Then perhaps I can keep an eye on the colonel –

And try to save him from the toils of that poison-ivy – poor innocent lamb!

Could this 1872 story be an earlier example? https://www.newspapers.com/clip/32775443/1872_feb_22_plain_jane/

LikeLike

Maybe an earlier usage, based on Jane Eyre? ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jane_Eyre … “Though facially plain, Jane is passionate and strongly principled, and values freedom and independence.”) https://www.newspapers.com/clip/32777277/1867_feb_20_plain_jane_eyre/

LikeLike

Many thanks for those two quotations.

The story entitled Plain Jane is particularly interesting because no term is added to ‘plain Jane’. It is difficult to know whether the author, Mattie Dyer Britts, was applying the pre-existing expression ‘plain Jane’ to the character named Jane, or was applying the adjective ‘plain’ to ‘Jane’ before the expression existed.

You may very well be right to point out a possible influence of Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre.

LikeLike