The English painter and engraver William Hogarth (1697-1764) made a series of eight paintings called A Rake’s Progress (1735). It depicts the story of a rich merchant’s son, Tom Rakewell, whose immoral living causes him to end up at Bedlam. In this painting, the eighth one, the fashionably dressed women have come to the asylum as a social occasion, to be entertained by the bizarre antics of the inmates.—image: Wikimedia Commons

MEANING

bedlam: a place or condition of noise and confusion

ORIGIN

Bedlam, as well as Betleem, Bedleem, Bethlem, etc., were early forms of Bethlehem; for example, in the Early Version (around 1382) of the Wycliffe Bible, the gospel of Luke, 2:4, is:

Sothly* and Josep stiȝede vp fro Galilee, of the cite of Nazareth, in to Jude, in to a cite of Dauith, that is clepid Bedleem, for that he was of the hous and meyne of Dauith.

(* The conjunction sothly merely connects this verse to the preceding one.)

In the King James Version (1611), this verse is:

And Joseph also wēt vp frō Galile, out of the citie of Nazareth, into Judea, vnto the citie of Dauid, which is called Bethlehem, (because hee was of the house and linage of Dauid)

The name was applied to the Hospital of St. Mary of Bethlehem, in London, founded as a priory in 1247, with the special duty of receiving and entertaining the bishop, the canons, etc. of the mother church, St. Mary of Bethlehem, as often as they might come to England. It was mentioned in 1330 as “an hospital” and in 1402 as a hospital for lunatics. In 1346 it was received under the protection of the city of London; on the Dissolution of the Monasteries, it was granted to the mayor and citizens, and in 1547 incorporated as a royal foundation for the reception of lunatics. Originally situated in Bishopsgate, it was rebuilt in 1676 in Moorfields, and in 1815 transferred to Lambeth. Since 1930, as Bethlem Royal Hospital, it has been at Bromley, Greater London.

When it was situated in Moorfields, Bedlam was a popular resort for sightseers. The Swiss travel writer César-François de Saussure (1705-83) gave the following account in a letter from London dated 17th December 1725:

A magnificent hospital occupies all the width of this square. It is one of the largest and handsomest buildings in London. Its frontage is said to resemble that of the Louvre in Paris and to be built on its model. This fine hospital, named Bethlehem or by abbreviation Bedlam, is the abode of a part of the lunatics of London. Its gate is superb, above it and on either side there is a statue representing a chained maniac. After passing it and then walking through a small court, you go up a small flight of steps and you enter the building. A long and wide gallery, stretching all along the edifice, gives access to a large number of little cells, where are shut up lunatics of every description, whom you can see through little windows let into the doors. Those who are inoffensive are wandering in the gallery. On the second floor are a corridor and cells like those on the first. This is where are locked up the dangerous maniacs who for the most part are chained. Several of them are horrible to behold. On holidays usually, numerous persons of both sexes, belonging to the lower middle and lower classes, go there in order to amuse themselves watching these pitiable creatures, but of whom several give, despite one’s qualms, many causes for laughter. On leaving this melancholy abode, you must give a shilling to the porter. If you happened to have no change and give him a crown piece to change, he would honestly keep the whole sum and return you nothing. As everyone is aware of this custom, I don’t think he often happens to be given any coin to change.

original text (modernised spelling – 1903 edition):

Un magnifique hôpital occupe toute la largeur de cette place. C’est un des plus beaux & des plus vastes édifices de Londres. On dit que sa façade ressemble à celle du Louvre à Paris & qu’elle a été bâtie sur son modèle. Ce bel hôpital, appelé Bethlehem ou par abréviation Bedlam, est la demeure d’une partie des fous de Londres. Son portail est superbe, au-dessus & de chaque côté il y a une statue représentant un forcené enchaîné. Après l’avoir passé & ensuite traversé une petite cour, on monte un perron & on entre dans le bâtiment. Une longue & large galerie, régnant tout le long de l’édifice, donne accès à un grand nombre de petites cellules, où sont renfermés les fous de toutes les espèces, que l’on peut voir par de petits guichets. Ceux qui ne sont pas dangereux se promènent dans la galerie. Au second étage, il existe un corridor et des cellules semblables à celles du premier. C’est là que sont renfermés les forcenés qui sont pour la plupart enchaînés. Plusieurs d’entre eux font horreur. Ordinairement les jours de fêtes, grand nombre de personnes des deux sexes de la petite bourgeoisie & du peuple se font un amusement d’aller voir ces objets dignes de pitié, mais dont plusieurs donnent, malgré qu’on en ait, bien des sujets de rire. En sortant de cette triste demeure il faut donner un sol au portier. S’il arrivait qu’on n’ait pas de la monnaie, & qu’on lui donne un écu pour le changer, il garderait honnêtement le tout, & ne rendrait rien. Comme chacun sait cette coutume, je pense qu’il ne lui arrive pas souvent qu’on lui donne quelque pièce à changer.

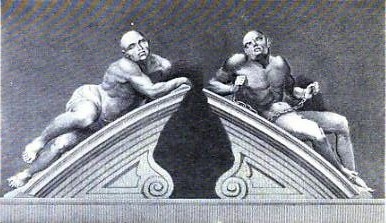

These two figures – mentioned by César-François de Saussure – were adorning the entrance portal to Bedlam in Moorfields; carved by Gabriel Caius Cibber about 1676, the figure on the left represents melancholy and the other raving madness or mania.—image: Wikimedia Commons

This is why the name Bedlam used to be synonymous with human degradation and callous indifference to it. The modern meaning, scene of mad confusion or uproar, of the common noun bedlam reflects conditions in earlier times.

In An hundred epigrammes (London, 1550), the English playwright and epigrammatist John Heywood (circa 1496-circa 1578) used Jack o’ Bedlam to mean a madman (Jack is a generic proper name for any man):

A lowse and a flea, set in a mans necke,

Began eche other to taunt and to checke.

Disputyng at length all extremitees

Of their pleasures, or discommoditees.

Namely this I heard, and bare awaie well.If one (quoth the louse) scrat within an ell

Of thy tayle: than forthwith art thou skippyng,

Lyke Iacke of bedlem in and out whippyng.

By extension, bedlam became synonymous with any lunatic asylum. It also came to be used to designate an inmate of any such asylum, or anybody deemed fit for such places; for example, in A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues (1611), under the headword affamé(e), famished, starved, Randle Cotgrave mentioned the proverb Vilain affamé demy enrage (literally, A famished peasant gets half mad), and translated it as A hungry Boore is halfe a bedlam.

In The Cronicle History of Henry the fift [sic] (Quarto 1, 1600), the English poet and playwright William Shakespeare (1564-1616) makes Pistol use bedlam as an adjective meaning mad in the question “art thou bedlem?”.

And Shakespeare uses bedlam humour to mean insane humour in The second Part of Henry the Sixt [sic] (Folio 1, 1623):

– York: We are thy Soueraigne Clifford, kneele againe;

For thy mistaking so, We pardon thee.

– Clifford: This is my King Yorke, I do not mistake,

But thou mistakes me much to thinke I do,

To Bedlem with him, is the man growne mad.

– Henry VI: I Clifford, a Bedlem and ambitious humor

Makes him oppose himselfe against his King.

I really appreciate the content and quality of your blog! Such a hidden gem, so glad I found it! 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you. That’s most encouraging!

LikeLiked by 1 person

you’re very welcome! I’ve been following your blog for quite a while and have been meaning to leave you a message!

LikeLike