MEANING

The phrase to take time, or opportunity, etc., by the forelock means to seize an opportunity.

Its earliest occurrence is from Menaphon Camillas alarum to slumbering Euphues, in his melancholie cell at Silexedra (London, 1589), by the English writer and playwright Robert Greene (1558-92):

Pesana hearing that he was lately falne sicke, and that Samela and hee were at mortall iarres; thinking to make hay while the Sunne shined, and take opportunitie by his forelockes, comming into his chamber, vnder pretence to visit him, fell into these termes; Why how now, Menaphon, hath your newe change driuen you to a night cap? Beleeue me, this is the strangest effect of loue that euer I saw, to freeze so quicklye the heart it set on fire so lately.

The English poet Edmund Spenser (circa 1552-1599) used a variant in Amoretti and Epithalamion (London, 1595):

SONNET. LXX.

Fresh spring the herald of loues mighty king,

In whose cote armour richly are displayd,

all sorts of flowers the which on earth do spring

in goodly colours gloriously arrayd.

Goe to my loue, where she is carelesse layd,

yet in her winters bowre not well awake:

tell her the ioyous time wil not be staid

vnlesse she doe him by the forelock take.

Bid her therefore her selfe soone ready make,

to wayt on loue amongst his louely crew:

where euery one that misseth then her make,

shall be by him amearst with penance dew.

Make hast therefore sweet loue, whilest it is prime,

for none can call againe the passed time.

French has the phrase saisir l’occasion par les cheveux, to seize opportunity by the hair, and variants; the following is from the Dictionnaire de L’Académie française (4th edition, 1762):

On dit figurément & proverbialement, Prendre l’occasion aux cheveux, pour dire, Profiter de l’occasion.

translation:

It is figuratively and proverbially said, To take opportunity by the hair, to say, To take advantage of opportunity.

ORIGIN OF THE PHRASE

The phrase refers to the representation described for example by the Roman fabulist Phaedrus (circa 15 BC-circa 50 AD) in Fabulæ Æsopiæ, versified Latin versions of fables in Greek prose then circulating under the name of Aesop:

Book V – VIII: Tempus

Cursu uolucri, pendens in nouacula,

caluus, comosa fronte, nudo corpore,

quem si occuparis, teneas, elapsum semel

non ipse possit Iuppiter reprehendere,

occasionem rerum significat breuem.

Effectus impediret ne segnis mora,

finxere antiqui talem effigiem Temporis.

translation into English verse by Christopher Smart (London,1913):

Opportunity

Bald, naked, of a human shape,

With fleet wings ready to escape,

Upon a razor’s edge his toes,

And lock that on his forehead grows—

Him hold, when seized, for goodness’ sake

For Jove himself cannot retake

The fugitive when once he’s gone.

The picture that we here have drawn

Is Opportunity so brief.—

The ancients, in a bas-relief,

Thus made an effigy of Time,

That every one might use their prime;

Nor e’er impede, by dull delay,

Th’ effectual business of to-day.

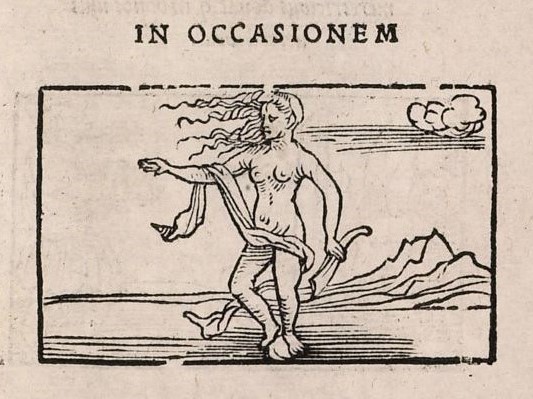

The following woodcut and text are from Emblematum liber (Augsburg, Germany – 1531), by Andrea Alciato (1492-1550), Italian humanist, legal scholar and author (source: French Emblems at Glasgow – Glasgow University, Scotland):

IN OCCASIONEM.

Lysippi¹ hoc opus est, Sycion² cui patria, tu quis?

Cuncta domans capti temporis articulus

Cur pinnis stas, usque rector, talaria plantis

Cur retines? passim me levis aura rapit

In dextra est tenuis dic unde novacula? acutum

Omni acie hoc signum me magis esse docet

Cur in fronte coma occurrens ut prendar, at heus tu

Dic cur pars calva est posterior capitis

Me semel alipedem si quis permitat abire.

Ne possim apprenso crine deinde rapi

Tali opifex nos arte tui causa aedidit hospes

Utque omnes moneam, pergula aperta tenet.

translation:

This image is the work of Lysippus¹, whose home was Sicyon².

– Who are you?

– I am the moment of seized opportunity that governs all.

– Why do you stand on points?

– I am always a leader.

– Why do you have winged sandals on your feet?

– The fickle breeze bears me in all directions.

– Tell us, what is the reason for the sharp razor in your right hand?

– This sign indicates that I am keener than any cutting edge.

– Why is there a lock of hair on your brow?

– So that I may be seized as I run towards you.

– But come, tell us now, why ever is the back of your head bald?

– So that if any person once lets me depart on my winged feet, I may not thereafter be caught by having my hair seized. It was for your sake, stranger, that the craftsman produced me with such art, and, so that I should warn all, it is an open portico that holds me.

The dialogue in Emblematun liber is a translation of an epigram by the Greek poet Posidippus (circa 310-circa 240 BC); in Adagiorum chiliades (Thousands of adages – 1508), an annotated collection of Greek and Latin proverbs, the Dutch humanist and scholar Desiderius Erasmus (circa 1469-1536) also gave a verse translation of this Greek epigram, and went into detail about the implications of the notion:

(from The Adages of Erasmus – selected by William Barker – University of Toronto Press, 2001)

Nosce tempus: Consider the due time.

Γνῶθι καιρόν, Consider the due time. Prominent among the familiar sayings of the Seven Sages³; ascribed, like most of them, to several authors and used by almost everyone. Hesiod:

‘Observe the mean: due time is best in all.’

Theocritus alludes to it in the eleventh idyll:

‘Some blooms in summer, some in winter blow.’

Isocrates too in the Ad Demonicum remarks that in all things there is less satisfaction if they are done out of due season. So important is it in all business to observe the due and proper time. The same message is to be found in the Greek maxims:

‘Small things are great when in due season given.’

And in another:

‘It always pays to know when time is ripe.’

Besides there is Pindar in the Pythians:

‘The proper time likewise is of all things the chief.’

And Horace’s familiar tag:

‘Sweet is folly in its proper place.’

Such is the force of Opportunitas, of Timeliness, that it can turn what is honourable into dishonour, loss into gain, happiness into misery, kindness into unkindness, and the reverse; it can, in short, change the nature of everything. In the beginning and ending of any business it has especial influence, so that the ancients, we may well think, had good reason to endow it with divinity, though in Greek this god is masculine, and his name is Kairos, Due Time.

Her image was represented in the old days as follows. She had wings on her feet and stood on a freely-turning wheel, and she spun very rapidly round and round. The forepart of her head was thickly set with hair, the back of it bald, so that her forehead could easily be grasped and the back of it not at all. Hence the phrase ‘to seize the opportunity.’ Thus both a learned allusion and an elegant image were produced by the unknown author of the line:

‘Long in the forelock, Time is bald behind.’

Besides which, it is a pleasure to add the epigram by Posidippus on this subject, which was unaccountably omitted by Poliziano⁴, and runs as follows:

‘“Where did the sculptor come from?”

“Sicyon.”

“And his name?”

“Lysippus.”

“And who are you, the subject?”

“Due Time, master of all things.”

“Why go on tiptoe?”

“I am always running.”

“Why have a pair of winged sandals on your feet?”

“I fly with the wind.”

“Why carry a razor in your right hand?”

“To show that I am keener than a razor’s edge.”

“And your hair, why so long over your face?”

“That he who is beforehand with me may seize it.”

“The back part, why so bald?”

“Because once I have run past a man on my winged feet, never for all his longing shall he seize me from behind. Such, stranger, did the artist make me, and set me in the forecourt to be a warning to you and your fellow men.”’

My version of these verses is not meant to compete with the Greek original; it is, as usual, uninspired and quite extempore, as the poem itself will have made clear even if I said nothing, my sole purpose being to make it intelligible to those who know no Greek.

Nor will it be off the point to add an epigram by Ausonius⁵, which, as Poliziano points out, is evidently derived from the Greek, although it differs in certain respects, and in particular by the addition of Remorse as Opportunity’s companion. The poem runs like this:

‘“The artist’s name?”

“Phidias.”

“What, the man who made the great statue of Athena?”

“Yes, and Jupiter, and I am the third of his masterpieces. I am the goddess Opportunity, so seldom seen, recognized by so few.”

“Why stand on a wheel?”

“I cannot stay still in one place.”

“And why those winged sandals?”

“I am always in flight, and the good fortune of which Mercury is patron I provide when I please.”

“Do you hide your face with hair?”

“I have no wish to be recognized.”

“But why bald behind?”

“That I may not be seized as I run past.”

“And who is your companion?”

“Let her tell you herself.”

“Tell me, pray, who are you?”

“I am the goddess who was not named even by Cicero himself, she who punishes what is done and not done in such a way that there are regrets afterwards; and so I am called Remorse.”

“Now I turn to you again: you must tell me what business she has with you.”

“When I take wing, she stays behind; if I pass any man by, she remains with him. You yourself, while you ask these questions and waste your time in idle curiosity, will find that you have let me slip.”’

original text:

Γνῶθι καιρόν, id est Noveris tempus. Celebratur in primis inter vii sapientum apophtegmata ac, ut alia pleraque, pluribus auctoribus ascribitur a nullo non usurpatum. Hesiodus:

Μέτρα φυλάσσεσθαι· καιρὸς δ’ ἐπὶ πᾶσιν ἄριστος, id est

Obervato modum, nam rebus in omnibus illud

Optimum erit, si quis tempus spectaverit aptum.

Huc allusit Theocritus in Idyllio Λ:

Ἀλλὰ τὰ μὲν θέρεος, τὰ δὲ γίγνεται ἐν χειμῶνι, id est

Verum alia aestivo atque hyberno tempore fiunt.

Quin et Isocrates ad Demonicum scribit iniucundum in omni re esse, quicquid intempestivum sit. Adeo cunctis in negotiis plurimum habet momenti temporis et opportunitatis observatio. Idem admonent Graecorum sententiae:

Ὡς μέγα τὸ μικρόν ἐστιν ἐν καιρῷ δοθέν, id est

Vel maxima est pusilla res loco data.

Rursus alia:

Καλὸν τὸ καιροῦ παντὸς εἰδέναι μέτρον, id est

Res bella cuncti nosse temporis modum.

Praetera Pindarus in Pythiis:

Ὁ δὲ καιρὸς ὁμοίως / Παντὸς ἔχει κορυφάν, id est Tempus pariter in omni re fastigium obtinet.

Item illud Horatii:

Dulce est desipere in loco.

Tantam vim habet opportunitas, ut ex honesto inhonestum, ex damno lucrum, ex voluptate molestiam, ex beneficio maleficium faciat et contra breviterque rerum omnium naturam permutet. Haec in aggrediundo conficiendoque negotio praecipuum habet momentum, ut non sine causa veteres videantur eam divinitate donasse, tametsi apud Graecos mas est hic deus appellaturque Καιρός.

Eius simulachrum ad hunc modum fingebat antiquitas. Volubili rotae pennatis insistens pedibus, vertigine quam citatissima semet in orbem circumagit, priore capitis parte capillis hirsuta, posteriore glabra, ut illa facile prehendi queat, hac nequaquam. Unde dictum est occasionem arripere. Ad quod erudite simul et eleganter allusit quisquis is fuit, qui versiculum hunc conscripsit:

Fronte capillata, post haec Occasio calva.

Sed libet et Posidippi super hac re carmen adscribere, quod quamobrem Politianus omittendum existimarit, admiror. Est autem huiusmodi:

Σίς πόθεν ὁ πλάστης; Σικυώνιος. Οὔνομα δὴ τίς;

Λύσιππος. Σὺ δὲ τίς; Καιρὸς ὁ πανδαμάτωρ.

Σίπτε δ’ ἐπ’ ἄκρα βέβηκας; Ἀεὶ τροχάω. Σί δὲ ταρσοὺς

Ποσσὶν ἔχεις διφυεῖς; Ἵπταμ’ ὑπηνέμιος.

Φειρὶ δὲ δεξιτερῆ τί φέρεις ξυρόν; Ἀνδράσι δεῖγμα,

Ὡς ἀκμῆς πάσης ὀξύτερος τελέθω.

Ἡ δὲ κόμη, τί κατ’ ὄψιν; Ὑπαντιάσαντι λαβέσθαι.

Νὴ Δία τἀξόπιθεν πρὸς τί φαλακρὰ πέλει;

Σὸν γὰρ ἅπαξ πτηνοῖσι παρατρέξαντά με ποσσίν,

Οὔτις ἔθ’ ἱμείρων δράξεται ἐξόπιθεν.

Σοῖον ὁ τεχνίτης με διέπλασεν εἵνεκεν ὑμέων,

Ξεῖνε, καὶ ἐν προθύροις θῆκε διδασκαλίην.

Quos versus nos ita vertimus, non quo cum archetypo Graeco certaremus, sed crassiore, sicuti solemus, Minerva planeque ex tempore, quod vel tacente me carmen ipsum indicaverit, videlicet ut intelligi duntaxat possint ab his, qui Graece nesciunt:

Quae patria artifici ? Sicyon. Quo nomine ? Nomen

Lysippo dictum est. Ipse quis es ? Loquere.

Illa ego cuncta domans Occasio. Cur age, pinnis

Insistis ? Volvorque ac rotor assidue.

Cur gemina in pedibus gestas talaria ? Dicam,

Huc illuc volucrem me levis aura rapit.

Quid dextrae sibi vult inserta novacula ? Signum hoc

Quod quavis acie sim mage acuta, docet.

Tecta capillitio facies quidnam admonet ? Illud

Quisque uti me, quoties offeror, arripiat.

Cur autem capitis pars posticaria calvet ?

Quem semel alatis praeterii pedibus,

Is quanquam volet inde cito me prendere cursu,

Haud liceat, simul ac vertero terga viro.

Hac itaque idque tua me finxit imagine causa,

Hospes, scalptoris ingeniosa manus,

Spectandamque domus hic prima in fronte locavit,

Scilicet ut cunctos et moneam et doceam.

Non ab re fuerit et Ausonianum epigramma subscribere, quod ut admonet Politianus, e Graeco videtur effictum, quanquam cum aliis nonnullis diversum tum illo potissimum nomine, quod hic additur Poenitentia comes. Carmen sic habet:

Cuius opus ? Phidiae, qui signum Pallados, eius

Quique Iovem fecit, tertia palma ego sum.

Sum dea, quae rara et paucis Occasio nota.

Quid rotulae insistis ? Stare loco nequeo.

Quid talaria habes ? Volucris sum. Mercurius quae

Fortunare solet, trado ego, cum volui.

Crine tegis faciem ? Cognosci nolo. Sed heus tu

Occipiti calvo es ? Ne tenear fugiens.

Quae tibi iuncta comes ? Dicat tibi. Dic, rogo, quae sis.

Sum dea, cui nomen nec Cicero ipse dedit.

Sum dea, quae facti non factique exigo poenas,

Nempe ut poeniteat, sic Metanoea vocor.

Tu modo dic, quid agat tecum. Si quando volavi

Haec manet, hanc retinent, quos ego praterii.

Tu quoque dum rogitas, dum percontando moraris,

Elapsam dices me tibi de manibus.

NOTES

¹ Lysippus was a Greek sculptor of the 4th century BC.

² Sicyon was a city state situated in the northern Peloponnesus between Corinth and Achaea.

³ The Seven Sages were ancient statesmen and philosophers, listed in Plato’s Protagoras: Chilon, Pittacus, Bias, Cleobolus, Periander, Thales and Solon.

⁴ Angelo Poliziano (1454-94) was one of the leading Italian humanists.

⁵ Decimius Magnus Ausonius (circa 310-circa 395) was a Roman poet.