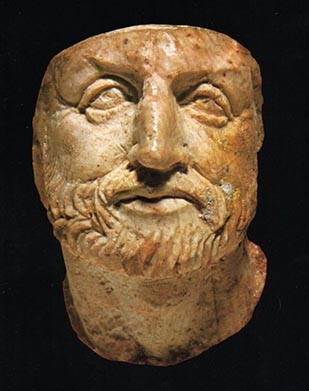

Philip II of Macedon – photograph: Greece.com

The phrase to appeal from Philip drunk to Philip sober and variants mean to urge someone to reconsider an unfavourable decision.

The original allusion is to Philip II (382-336 BC), King of Macedon, whose response to such an appeal is reported by the Roman historian and moralist Valerius Maximus (floruit 14-37 AD) in Facta et Dicta Memorabilia (Memorable Deeds and Sayings). Chapter 2 of Book 6 is titled Libere Dicta aut Facta (Frank Statements or Actions); after the Roman Stories, the first of the Foreign Stories is as follows:

Inserit se tantis uiris mulier alienigeni sanguinis, quae a Philippo rege temulento immerenter damnata, prouocare se iudicium uociferata est, eoque interrogante ad quem prouocaret, ‘ad Philippum’ inquit, ‘sed sobrium’. excussit crapulam oscitanti ac praesentia animi ebrium resipiscere causaque diligentius inspecta iustiorem sententiam ferre coegit. igitur aequitatem, quam impetrare non potuerat, extorsit, potius praesidium a libertate quam ab innocentia mutuata.

(translation: Henry John Walker – 2004)

A woman from a foreign nation joins these great men. She had been wrongly convicted by King Philip, who was drunk at the time. She shouted out that she was appealing against the judgement, and when Philip asked her who she was going to appeal to, she said, “To Philip, but not until he is sober.” He had been gaping stupidly, but she knocked his drunkenness out of him. By her determination, she forced him to come back to his senses, inspect her case more carefully, and make a more just decision. She had been unable to obtain justice so she got it by force, and she borrowed strength from her frankness rather than from her innocence.

In the chapter Of glotons and dronkardes of The Shyp of Folys of the Worlde (1509), an adaptation by the British poet and clergyman Alexander Barclay (circa 1484-1552) of Daß Narrenschyff ad Narragoniam (1494), by the German humanist Sebastian Brant (1458-1521), the situation is different: it is to Philip II’s son, Alexander the Great (356-323 BC), that a knight, who has defeated him in a game of chess, appeals:

I rede also howe this conquerour myghty

Upon a season played at the Chesse

With one of his knyghtes which wan fynally

Of hym great golde treasoure and rychesse

And hym ouercame / but in a furyousnes

And lade with wyne / this conquerour vp brayde

And to his knyght in wrath these wordes saydeI haue subdued by strength and by wysdome

All the hole worlde / whiche obeyeth to me

And howe hast thou alone me thus ouercome

And anone commaundyd his knyght hanged to be

Than sayde the knyght by right and equyte

I may apele. syns ye ar thus cruell

Quod Alexander to whome wylt thou apellKnowest thou any that is gretter than I

Thou shalt be hanged thou spekest treason playne

The knyght sayd sauynge your honour certaynly

I am no traytoure / apele I woll certayne

From dronken Alexander tyll he be sober agayne

His lorde than herynge his desyre sounde to reason

Differryd the iustyce as for that tyme and seasonAnd than after whan this furour was gone

His knyght he pardoned repentynge his blyndenes.

And well consydered that he shulde haue mysdone

If he to deth had hym done in that madnesse

Thus it apereth what great unhappynes

And blyndnes cometh to many a creature

By wyne or ale taken without measure.

In The boke named the Gouernour (London, 1537), the English diplomat and humanist Thomas Elyot (circa 1490-1546), after telling the story of a soldier who urged King Philip to give a more considered judgement when thoroughly awake, wrote:

Semblably hapned by a pore woman, agaynste whom the same kynge had gyuen iugemēt, but she as desperate, with a loude voice, cried, I appele, I appele. To whom appelest thou sayde the kynge? I appeale, sayde she, from the, nowe beynge dronke, to kynge Philyp the sobre. At which wordis, though they were vndiscrete and foolishe, yet he nat being moued to displesure, but gatherynge to hym his wyttes, examined the matter more seriously: wherby he fyndyng the pore woman to susteyn wronges, reuersed his iugement, and according to truth and iustyce, gaue to her that she demanded.

The earliest known use of the phrase is from Letters to the Inhabitants of the Town and Lordship of Newry (Dublin, 1793), by Joseph Pollock, a barrister who had been nominated from the town of Newry to the Convention for parliamentary reform and equal religious rights at Dungannon, in County Tyrone, Ireland:

The more I thought of the measures to be proposed to the Convention, the less I liked them. An appeal from the Committee to the Convention itself might not be, exactly, one “from Philip inflamed to Philip sober;” but it seemed necessary.—If it should not succeed, it would be a sort of record, that other measures had been, at least, proposed, and it would be an ultimate to the constituent body, or to the people at large.

In the Seymour Tribune (Seymour, Indiana) of 26th January 1984, the American author William F. Buckley Jr. (1925-2008) used the image in a different sense:

Doctors who specialize in the problems of alcoholics tell you that when brother-in-law Phil drops by on one of his binge-visits, what you should do is secretly record his conversation, and then the next day, quick while he’s sober, play it to him, to visit on Philip Sober the awful sound of Philip Drunk—and maybe that way persuade him to visit Alcoholics Anonymous.