The phrase to bite (on) the bullet means to confront a painful situation with fortitude.

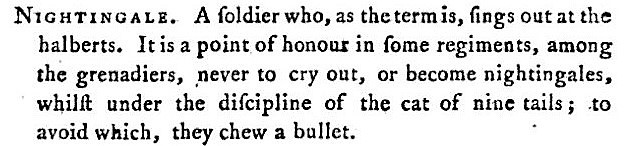

It originated in the practice consisting, for a soldier, in biting on a bullet when being flogged. The English antiquary and lexicographer Francis Grose (1731-91), who had been a soldier, mentioned it in A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (2nd edition – London, 1788):

Nightingale. A soldier who, as the term is, sings out at the halberts. It is a point of honour in some regiments, among the grenadiers, never to cry out, or become nightingales, whilst under the discipline of the cat of nine tails; to avoid which, they chew a bullet.

In the same edition of the dictionary, Grose explained the manner in which halberds were used in corporal punishments:

Spread Eagle. A soldier tied to the halberts in order to be whipped: his attitude bearing some likeness to that figure, as painted on signs.

I have found several mentions from the second half of the 19th century of the practice of biting on a bullet when being flogged. For instance, this is from The Fife Herald (Cupar, Fife, Scotland) of 31st January 1867:

THE PHILOSOPHY OF FLOGGING.

(From the Lancet.)

It is very interesting to note the effects of the application of the cat. Last week, two garotters [sic] received at Leeds Gaol a couple of dozen lashes a-piece, and those who have read the accounts have doubtless been surprised at the apparently slight effects produced upon the skin. The lashes of the cat were nearly a yard long, and at the extremity of each were three hard knots. […] We are anxious to point out that the results apparent to the naked eye are a not sufficient guage [sic] of the intensity of the punishment, or of the changes produced in the tissues of the body. […] There is spasm of the whole muscles of the back, especially the deep ones. When a man is about to receive a blow, he puts himself on his guard and his muscles also; he plants his foot firmly and contracts his whole muscular system. In operations, before the blessings of chloroform were known, the patient about to be operated on grasped with a death-like grip the table whereon he was placed; and the same sort of condition was intended to be brought about by the biting of the bullet placed in the mouth of the soldier about to flogged. In all these cases the muscles are placed on their guard, and, being elastic, a great deal of injury might be inflicted without sensible harm.

Likewise, on 2nd November 1890, The Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) published Soldiers’ Punishment, about “the dreaded cat-o’-nine tails in the British army”:

“It’s considered bad form to groan or cry out when under the cat,” said a Sergeant of the Connaught Rangers, “and you rarely hear a soldier hollering, particularly an Irishman. The poor fellow puts a bullet between his teeth and takes a firm grip of it, and this helps him to keep his mouth shut. Sometimes a man bites through and through the bullet in his pain, and I’ve seen some of them spit it out all chewed to lead dust when the flogging was over. Without the bullet a man is likely to bite his tongue off, as I saw happen once in China, when the man at the end of the flogging turned and grinned at the Colonel with his bleeding tongue between his teeth—a disgusting sight.

The earliest known user of the phrase was the British novelist, short-story writer and poet Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) in The Light That Failed, published in instalments in several newspapers in 1890; for example, on 14th December of that year, The Post-Dispatch (St. Louis, Missouri) had:

“My God! I’m blind! I’m blind, and the darkness will never go away.” He made as if to leap from the bed, but Torpenhow’s arms were round him, and Torpenhow’s chin was on his shoulder, and his breath was squeezed out of him. He could only gasp, “Blind!” and wriggle feebly.

“Steady, Dickie, steady!” said the deep voice in his ear, and the grip tightened. “Bite on the bullet, old man, and don’t let them think you’re afraid.”

The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Mercury (Leeds, Yorkshire) of 7th July 1954 published France likes the look of her new Prime Minister, in which Brian Beedham cleverly extended the phrase when evoking “the familiar spectre of the European Defence Community”—Pierre Mendès-France (1907-82) was the new Prime Minister and Jean Michel Guérin du Boscq de Beaumont (1896-1955) his Secretary of State at the Foreign Office:

If the prophets are right in saying that EDC as it exists at the moment is doomed, then the end is likely to come not with the bang of a Parliamentary vote but in a fading whimper of interminable argument.

Two camps on EDC

The supporters of a European Army, however, have not lost all hope. It is significant that M. Guérin de Beaumont himself is in their camp, and the Cabinet are divided almost exactly in two on the subject. At the moment the leaders of the two factions are meeting in an attempt to agree on conditions which would enable France to speak with a united voice. If they seem to have a modest chance of success (it can be put no higher than that) it is for two reasons.

The first is the shift of emphasis that has occurred during the last year in French objections to EDC. It is no longer the idea of putting rifles into German hands that chiefly arouses a Frenchman’s anger: what he dislikes most is the fact that EDC would tie up French troops which he would prefer to use in policing the trouble-areas of the French Union. The second is the fact that if M. Mendès-France succeeds in bringing to an end the seven-year-old war in Indo-China, fewer troops will be needed for such oversea work. If this happens it is just possible that Frenchmen may be willing to swallow the rest of their objections and bite the European bullet.

FOLK ETYMOLOGY

No evidence supports the oft-repeated tale that the phrase to bite (on) the bullet originated in the former practice of giving a wounded soldier a bullet to bite on when undergoing surgery without anaesthetic.